Recent Articles

The Curse of POLTERGEIST’S Curse: One Final Bonus Spielberg Article

Just in time for Halloween, let’s extend Spielberg Summer 2 deep into October by digging into the other movie in 1982 that cemented his legacy, even though it was technically directed by Tobe Hooper. POLTERGEIST has an unfortunate legacy of being a “cursed film”, an infuriating moniker that masks what made this movie haunt all these years later. It’s here!

It’s funny how much suburbs freak people out.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the argument against them. Rows of houses that all look the same, built in the relative nowhere on top of land that previously contained who-knows-what, filled with people who admittedly can be kind of recluses and pains in the asses….okay, well, maybe it’s not that funny how much suburbs give some the heebie-jeebies. But, it must be said that, having grown up in a very middle of the road suburb, there often isn’t much to them. They’re mostly a little boring, if anything.

But the fascination with them in visual media remains, with their supposed representation of the American dream; they’re great places to have 2.5 kids; you might even luck out and get a white picket fence. Of course, just like America itself, that dream can often cloud sinister secrets, or dastardly deeds. In the 80’s and 90’s, this fascination reached a fever pitch. Movies like THE ICE STORM, EDWARD SCISSORHANDS, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, and the granddaddy of them all, BLUE VELVET, make these homogenized communities a place of dread.

However, there’s a major player from the 80s that seems to not get the same amount of shine, possibly because it has a different legacy all its own, the “cursed film”, a moniker I’m going to scream about by the end of this. But it’s also heavily associated with Steven Spielberg, the man who wrote and produced the damn thing, and only isn’t considered the director by technicality. Thus, it seemed only right to extend Spielberg Summer 2 just one more time, a whole month into autumn, in order to cover the other “non-Spielberg Spielberg movie with dicey behind-the-scenes stories”.

I speak, of course, of POLTERGEIST. It’s here!

POLTERGEIST (1982)

Starring: Craig T. Nelson, JoBeth Williams, Beatrice Straight, Heather O’Rourke, Dominique Dunn, Zelda Rubinstein

Directed by: Tobe Hooper

Written by: Steven Spielberg, Michael Grais, Mark Victor

Released: June 4, 1982

Length: 114 minutes

POLTERGEIST tells the story of the Freeling family, residents of Cuesta Verde, California. They live a relatively normal life; dad Steven is a thriving real estate agent, while mother Diane stays at home to raise their three children Dana, Robbie, and Carol Anne. Everything starts going to pot when little Carol Anne starts becoming fascinated with the static in the television. At a certain point, a hand reaches out from the TV, and an earthquake hits their suburban neighborhood, leading to the iconic moment where Carol Anne turns to her family and simply states “they’re here…”

It’s not long before Carol Anne is pulled through the TV by the titular poltergiest (although, may there be more than one poltergiest in the house?), and the Freelings find themselves in a mad race to get her back, by any means neccessary. Along the way, we meet the memorable Tangina Barrons (Zelda Rubinstein), learn just what sin was committed on this land to cause this poltergeist intrusion, and and see just what “the Beast” looks like up close.

As mentioned, POLTERGEIST is officially a Tope Hooper Joint. Yes, it was Spielberg’s idea from the beginning, having started developing the idea for it all the way in the late-70’s. Alas, a contractual technicality kept him from actually manning the director’s chair while still working on E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL, which is where Hooper started getting involved. How much Hooper really got to direct, though, depends mainly on your point of view, as well as who you believe. I don’t know that I have a particular dog in this fight, necessarily, but…the more you look at it, the more undeniable it becomes that this really is a Spielberg movie being pushed through a Hooper filter.

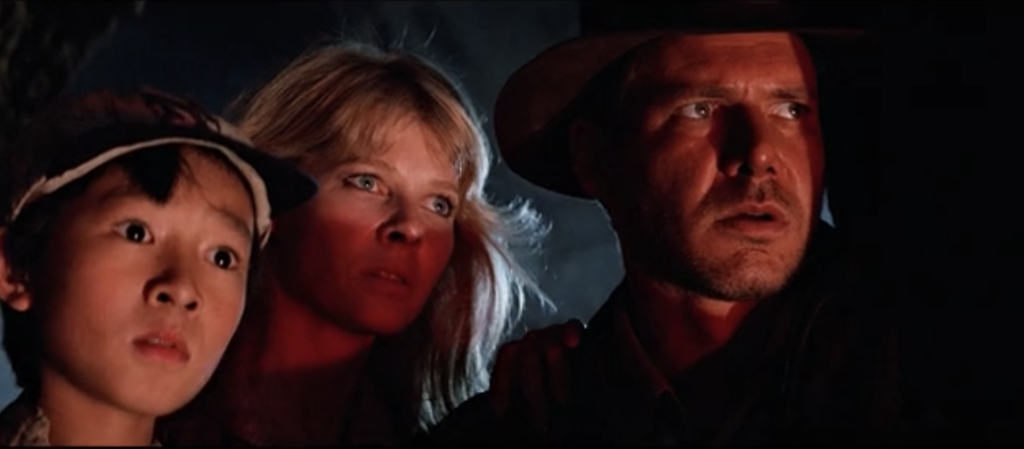

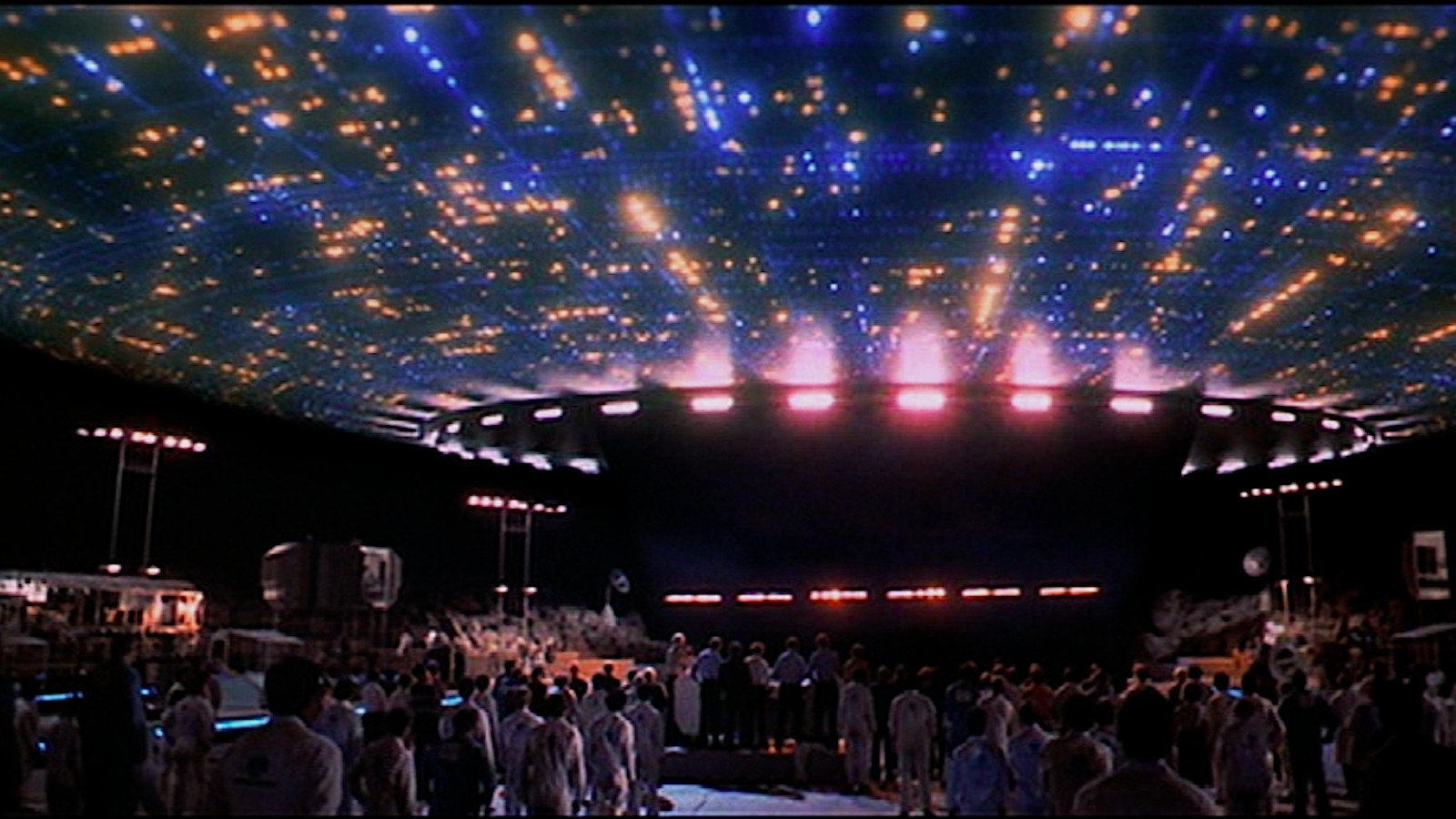

Let’s take a look at the tape: we have a movie about a missing child, starring a family that is mostly figuring out how to hold together through adversity, being haunted by something ethereal (or at least not precisely of this world), taking place in a true Anywhere, USA. I’m not sure you get any more quintessential 70s/80s Spielberg than that. Yes, POLTERGEIST undoubtedly has a harder edge than anything we’ve seen in CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND or E.T., which is where the dude who gave us THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASSACRE comes in, but you can’t deny how neatly this fits into Spielberg’s filmography up to this point. Hell, the neighborhood this takes place in feels functionally identical to the one in which the Taylors reside in E.T.

Speaking of, I find both movies’ unique view on the suburbs to be rather telling. In both, the neighborhood is a place where intensely personal emotions reside. In E.T., the sobering sadness of divorce permeates the air at the beginning, before a friendly, child-like alien is able to show everyone the light. In POLTERGEIST, there’s not so much a sadness as there is a persistent, steady fear of what’s just outside, a perspective tailor-made for the inherently isolating nature of the remote suburbs. The scariness of what’s just outside our grasp, what we can’t quite see….that kind of energy is what probably freaks people out about these kinds of neighborhoods in the first place.

Obviously, POLTERGEIST’s fascination with (and light condemnation of) television is one of the more well-known things about it (please see: the aforementioned iconic “they’re here” scene). And, man, does all of that stuff hit super hard forty-plus years later. The concept of losing a small child inside of an electronic screen…eerily prescient, borderline on-the-nose, imagery! But the specific type of television the movie seems to fixate on is that hyper-specific, defunct kind of TV: the “sign off” broadcast that networks would do at the end of the night, when the schedule ended. The images of Mount Rushmore and fighter jets flying across the sky! The playing of the Star-Spangled Banner! Then…test patterns! It’s a reflection of a simple time.

Here’s my simple proposal: let’s bring the “sign off” broadcast, but for social media. This feels like a reasonable compromise to the issue of Facebook and TikTok destroying our brains, but all of us also being beholden to the phone in our pocket. Keep it all, ban nothing, but at midnight, the X app starts playing the national anthem and gives you a video of Grand Canyon stock footage, then it just shuts off until 6 am. Would anyone besides the country’s biggest degenerates have an issue with this?

Anyway, POLTERGEIST.

I sometimes get uncomfortable with people’s fascination regarding movies that have a lot of unfortunate backstory to them, especially when those movies get branded as “cursed”. In POLTERGEIST’s case, yes, it’s true, it features two child actors who reached very sad and very abrupt ends to their life. Heather O’Rourke’s death in 1988 at the age of 12, essentially due to cardiac arrest, was tragic enough, but Dominique Dunne’s 1982 murder at the hands of her boyfriend is even more chilling. They’re both impossibly sad outcomes to the lives of two people who should still be here.

But the whole “POLTERGEIST is cursed!” narrative has always driven me a little crazy. It’s a thing people insist upon, and O’Rourke and Dunne’s demises get constantly pointed to as proof that the movie was filmed on an ancient burial ground or something. But…to be blunt, I don’t know that an actor dying six years after a movie’s release constitutes a curse to me. There are other things people point to in order to bolster the whole “the movie is cursed!” thing; evidence includes Julian Beck, an actor from 1986’s POLTERGEIST II (most well known for being a completely different movie) dying as a result of stomach cancer, an affliction he had been diagnosed with three years prior, as well as a rumor that Spielberg had *gulp* real skeletons on the set, instead of plastic ones. Holy fuck, this movie is cursed!

Yet, the perception of a curse remains, even earning POLTERGEIST a spot on the first season of Shudder’s docu-series Cursed Films. And, I’m not here to crap on anyone’s belief systems; if curses are real to you, who am I to say you’re wrong? But I’m not exactly sure why people glomb onto this particular case so much, especially since the actual events that happened are so sad. My only real theory is that the idea that a movie was cursed is an easier thing to deal with than the fact that sometimes kids get sick and die for no reason, and teenagers get murdered for no reason. But the end result of trying to grapple with that is a narrative where we seem to be blaming the vicious slaying of a teenager on the movie she was in.

It’s a shame, especially since there’s much more interesting things to talk about with this movie. The suburban setting is sufficiently creepy in its seeming innocuousness, and the way that benign objects in and around the house are used against its inhabitants may stay with you (the aforementioned television being the most predominant example, but how about that giant fucking tree outisde Robbie’s room?) POLTERGEIST is also a movie filled with memorable performances, with the eccentric Zelda Rubinstein and the wunderkind O’Rourke getting most of the shine. However, I’ve always been taken with what a presence Craig T. Nelson is in this. This isn’t ultimately a movie about a family trying to come back together, so much as they are just trying to hang on. His calm and steady performance helps sell that so well. I’m not sure it would have worked with someone else in his shoes.

It’s also interesting to see where Tobe Hooper is able to make his mark, even if it’s around the edges. His most obvious influence is in some of the gorier moments; stuff like the investigator’s face getting ripped off feels distinctly un-Spielbergian, to say the least. But I also think simple moments of building dread, like the set-up and payoff of the clown toy that eventually comes to life and starts attacking the kids, has a harder edge to it than similar moments in other Spielberg movies up to that point. Spielberg movies can sometimes be distressing, yes: E.T. dying, the opening of the Arc of the Covenant…but genuine horror isn’t something he normally trades in. You can probably look to Hooper, the man who brought us THE TEXAS CHAINSAW MASACRE, at least a little bit for POLTERGEIST’s legitimate scares.

At the end of the day, though, POLTERGEIST is an essential part of Steven Spielberg’s legacy, while remaining just a curious blip on Hooper’s. Its release (June 4th) a week before E.T. (June 11th) caused enough of a rumble at the box office that both Time and Newsweek felt comfortable declaring 1982 “The Summer of Spielberg”. And when you take the macro view on American culture from that point forward, it’s an assessment that’s difficult to argue with. These two movies, plus the rise of Amblin Entertainment putting out films like GREMLINS, BACK TO THE FUTURE, THE GOONIES, and all your other favorite 80’s childhood treasures, seemed to have forever altered what we expected from blockbuster family entertainment. Science fiction and adventure would become in vogue, with tons of imitators rising from the muck to try to cash in on the Spielberg machine. How many movies in the 80s and 90s centered around some kind of creature? Or normal, middle-American coded family? CRITTERS, MAC AND ME, HARRY AND THE HENDERSONS, STAR KID, FLIGHT OF THE NAVIGATOR, THE LAST STARFIGHTER…..the list goes on and on ad infitium. You almost certainly have the one-two punch of E.T. and POLTERGEIST to thank for all of that.

It’s too bad the movie is cursed, though. You can only imagine what its influence and power would have been without that.

Spooky Spielberg Bonus: Entering the TWILIGHT ZONE MOVIE!

This week, Spielberg Summer goes into overtime with a dip into TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE! Yes, it’s an anthology film most famous for the behind-the-scenes tragedy that arguably ended the New Hollywood era. Is anything in the movie (including the section directed by Spielberg himself) strong enough to overcome this dark shadow?

Confession: I don’t really know The Twilight Zone. Yeah, yeah, I know, shut up.

I mean, yes, I’ve undoubtedly seen a few episodes. How could you miss it? My mom was a fan of the show, and likely showed me a pair of installments as they came up on TV Land. Even if she hadn’t, much like some of its contemporaries like I Love Lucy or Leave It to Beaver, you can probably find an episode playing on some channel at any point of the day (and in a world of Pluto TV, that probability becomes a certainty). But it was never a mainstay on our television. I’ve always meant to get around to it, but I just haven’t up to this point.

However, I did find myself with an interesting opportunity to dip into the broader world of The Twilight Zone. Because, as I started wrapping up my latest series of Steven Spielberg reviews, this time diving into his 80s filmography, I realized, “oh yeah, wait, he technically helped direct another 80s movie”. That, of course, being THE TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE, the 1983 anthology film where Spielberg collaborated with John Landis, George Miller, and Joe Dante to recreate a touchstone television series that meant a lot to them all growing up.

Of course, the movie ended up having a much darker legacy, with the untimely (wildly preventable) deaths of a few actors, the dissolution of some friendships, and an extremely deflated, slightly sinister, energy throughout the proceedings as a result. It’s a difficult thing to discuss, and one can easily Google all the behind-the-scenes catastrophes that resulted from its creation (suffice to say though, TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE wasn’t included in a series called Cursed Films for no reason). But…I admit to being curious about what the actual viewing experience would be for me, me knowing full well how John Landis basically killed Vic Morrow, but not knowing full well much of The Twilight Zone’s biggest hits. It may make for an odd time, but..I had to know.

Besides, it’s October. Seems as good a time as any to extend the Spielberg series one more week. So let’s do it! Let’s enter THE TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE!

Prologue

Starring: Albert Brooks, Dan Aykroyd

Written by: John Landis

Directed by: John Landis

A driver and a passenger discuss Creedence Clearwater Revival, old TV theme songs, AND their favorite Twilight Zone episodes before one shows the other something really scary…

First off, I was surprised at how much this resembled the kind of scene that Quentin Tarantino would later make a whole career out of. Two recognizable actors? Check! A dialogue-heavy sequence centered almost exclusively around discussion of old media? Check! Classic rock needle drop? Check! Quick and memorable turn at the end? Check, check, check!

Look, I do think it’s a little odd to open the TWILIGHT ZONE movie with a tacit recognition that The Twilight Zone TV show exists in-universe; that kind of meta reference feels a little at odds with the original series. But, beyond that, I thought this was a fairly solid opening salvo. Both Brooks and Aykroyd are in their fine 80’s form, cool CCR song, nice twist at the end (the kind that undoubtedly would have scared me as a kid)...Landis admittedly gets this movie off to a good start! If he had just stopped there, Hollywood history would have changed forever!

Time Out

Starring: Vic Morrow, Doug McGrath, Charles Hallahan, John Larroquette

Written by: John Landis

Directed by: John Landis

Bill Connor is at the lowest point in his life, and he decides to lash out in a racist tirade at a bar. However, he’ll be changed forever as he walks through the door and finds himself having time-traveled to 1940’s Nazi-occupied France. Worse, everyone assumes he’s a Jewish runaway….

Alas, he hadn’t stopped there. He would go on to direct the first segment of TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE, and now we gotta immediately lean into what makes this movie such an infamous entry in Hollywood canon.

Look, I’m not going to go into the reckless and immoral decisions that led to Morrow and two child actors getting decapitated on the set of this segment; it’s easily the most famous thing about the movie, and the way it essentially destroyed any momentum on its development, Landis and Spielberg’s friendship, and maybe the New Hollywood era? It’s been covered a lot, and for good reason. It’s maybe the worst thing that’s ever happened on a film set, and it’s shocking that the whole affair didn’t end Landis’ career on the spot.

I will say that the onscreen result of this accident, which occurred during the filming of “Time Out”’s original ending, is that the segment now actually has no shape, or even point? We begin with the racist ramblings of Bill Connor (Morrow) at a bar, as he blames blacks* and Jews and immigrants for all of his troubles (a scene that would have been outrageously broad and on the nose if it didn’t now resemble the net average Facebook comment). He stumbles out to find himself in Nazi-occupied France, where everyone assumes he’s Jewish. As he flees the Gestapo, he then finds himself a presumed black man in the clutches of the KKK. Falling down He then awakens in a Vietnamese village, one being massacred by American soldiers. He then arrives back in occupied France, where he’s stuffed into a railcar, off to a concentration camp. Despite him screaming for his friends, who are now walking out of the bar, nobody can help Bill now.

*Well, I’m saying blacks. Connor uses, um, stronger language, utilizing a word that gets said a lot in this segment.

Presumably, the botched scene, where Bill saves two Vietnamese children from the crossfire of American troops, would have provided some sort of catharsis for our main character, as he learns that maybe being passed over for a promotion isn’t the worst atrocity someone can face, providing him some perspective, and perhaps spurring change. We can only presume, though, because “Time Out” in its final form basically has no ending. Like, I was shocked when the movie just…moved on to the next segment.

It’s actually not even a story in its current state. We watch a miserable human being get subjected to cosmic misery, then carted away to die a miserable, torturous death. Cool! Don’t get me wrong; “are avowed racists worthy of redemption?” is a very real question in culture right now, and I suppose, to describe it, one could make the argument that the current ending of “Time Out” is the only just and moral one. And…maybe! But the end result is one of those nasty, punitive stories where there’s nothing to be gleaned from it, nothing to learn, nothing to do. Just suffering being passed down. Couple that with the fact that, oh yeah, the segment is compromised because the director killed three people, and I cannot imagine a more catastrophic, confusing start to a movie that should have been a nice slice of anthology fun.

Although, if you’ve ever wondered what it would sound like if John Larroquette said the N-word with a hard R, do I ever have a movie rec for you!

Kick the Can

Starring: Scatman Crothers, Bill Quinn, Selma Diamond, Helen Shaw

Written by: George Clayton Johnson, Richard Matheson, Melissa Matheson

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Here it is, the segment directed by the man of the hour, the reason I’m even reviewing this movie in this space in the first place, a nice dose of whimsy and sentimentality after the bitter flavor of the first segment!

Aaaaaand…it’s the worst one of the whole movie. Damn!

It’s not to imply that “Kick the Can” is unwatchable or anything. A direct remake of an iconic Twilight Zone episode, it has a sweetness to it that nothing else in the movie really has, which makes it presumably a good match between material and director. Scatman Crothers puts in his usual lovely and disarming performance, even if his role actually really compromises the story (more on that in a bit). Finally, unlike the story of Bill Connor, the story here is something I think we can all connect and see ourselves in: I remember at the age of 12 feeling like childhood had completely passed me by. I can only imagine what 82 will feel like.

But…”Kick the Can” feels fairly surface-level to me, and a little beneath what Spielberg was already capable of. The direction is functional, if pedestrian, although I’m willing to extend Steven a ton of grace on this one. A serious friendship was violently crumbling during the production of this damn movie, after all, so I can forgive him for not feeling especially creative. But I get the feeling that, even if Spielberg were on his A+ game, “Kick the Can” as written would feel below par.

I have not seen the original episode and, thus, cannot compare the two versions. However, I do suspect I would enjoy the TV episode more. In that iteration, a nursing home resident discovers the secret of youth: acting young. It sounds like the “you’re only as old as you feel” concept made literal: the idea of everyone turning into children and running off into the woods, freed from the perception of what being old is supposed to feel like (again, this is only my interpretation of the episode based off a summary on Wikipedia) is a strong one.

In the movie version, though, a magical new resident kinda…casts a spell on the residents to turn them into kids, then they all realize there are real benefits to being old (like their families recognizing them, or maintaining their current memories), and most turn back into their normal ages, save one. One particular crotchety resident, however, realizes from the experience that, hey, he doesn’t have to act old just because he is. It feels like two stories reaching the same conclusion, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with pointing out that, hey, youth is often severely overrated! But I think the way the movie version arrives there is needlessly complicated; I won’t weigh in on whether or not Crothers’ character, as charming as he is, counts as perpetuating the “Magical Negro” trope or not, but I do think him being something akin to a wizard needlessly obfuscates a story that felt quite literate without it. Mr. Bloom is ultimately just not really needed, and felt like an added device that allowed for Matheson to put his own stamp on the story.

Is “Kick the Can” better than “Time Out”? Yes, in the sense that it’s a complete thought, although it’s a real toss-up as to whether I prefer a finished story that isn’t very clear or, really, all that interesting, versus a very provocative story that ends halfway through because the guy telling me the story decided to kill three people instead. Who’s to say?

Luckily, TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE picks up big time after this…

IT’S A GOOD LIFE

Starring: Kathleen Quinlan, Nancy Cartwright, Kevin McCarthy, William Schalert

Written by: Richard Matheson

Directed by: Joe Dante

Helen Foley takes a little boy, Anthony, from a roadside bar back to his family’s house. Everyone seems congenial and inviting. They also seem a little too accommodating to Anthony’s particular habits, like watching TV all day, or eating insane junk food for dinner. More than anything, they seem terrified of the child…

Aaahh…now that’s the good stuff.

The second half of TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE provides us adaptations of two of the most recognizable episodes of The Twilight Zone of all time, stories saturated enough in popular culture that I instantly went “oh, this is one where Bart Simpson can turn people into whatever he wants using his mind” as soon as this one got going. Again, never seen The Twilight Zone! But, the idea of a child who has boxed in the adults around him to serve his every whim, lest there be dire consequences, is such a potent (and timely) idea that it’s no wonder it’s remained in the public consciousness over sixty years later.

Interestingly enough, this adaptation of “It’s a Good Life” also kind of feels like an episode of The Simpsons. This segment feels so much like a cartoon, which is such an arresting, and appropriate, choice to make. But what else would you expect from a director like Joe Dante? Dante is one of those directors whose filmographies I really ought to do a deeper dive on one of these days, but suffice it to say that “putting the world of cartoons into the world of reality” is one of his signature touches, elevating even his lesser works (like, SMALL SOLDIERS isn’t exactly a good movie, but, boy, are those damn toys memorable). The way little Anthony’s house looks, these bright walls at odd angles…it just hits a specific spot in my heart.

And the fucking puppets. The depiction of literal two-dimensional cartoon characters being brought into 3D could go any number of ways. Here, though, Dante picks the exact right blend of “fun and tactile” with “grotesque”. Look at that fucking rabbit!

Or whatever the fuck this guy is supposed to be!

The design here is so fun and interesting to look at, even as you kind of want to look away. There’s not a doubt in my mind that this would have been seared into my brain as a kid, had I seen it at the time.

What really makes “It’s a Good Life” stand out over the first two segments, though, is that it feels like a complete story with something to chew on. Helen’s journey from Point A to Point B here is actually pretty interesting; she starts off as a somewhat demure teacher who appears, for all intents and purposes, lost. By the end of the twenty-or-so-minute runtime, she ends up being the only adult Anthony seems to trust, someone who will help cultivate his powers, not run from them. Anthony, it turns out, controls people with his mind because he’s afraid of being abandoned. In this sense, Helen and Anthony are well-matched. She won’t abandon him. They need each other. As they drive off, life sprouts all around them. Beautiful, bright flowers spring to life all along the road.

This ending also seems to be a deviation from the episode’s original ending, where the little kid causes a snowstorm that will assuredly doom and starve the rest of the town. Nice bleak little note, to be sure, but the movie segment’s ending really worked for me, too. Somehow, this insecure, demonic child (who removed his sister’s mouth and left her basically comatose in front of a blaring TV! He’s a real asshole!) is able to find someone who’s willing to cultivate him. Dante turns this into almost like a fairy tale.

Of course, there’s something to be said for staying faithful to a classic episode…

NIGHTMARE AT 20,000 FEET

Directed by: George Miller

Written by: Richard Matheson

Starring: John Lithgow

John Valentine is a nervous flyer who finds himself on a flight stuck in a severe storm. Despite attempts from staff to calm him down, he can’t settle. And that’s before he sees the gremlin wreaking havoc on the plane’s wing…

I’m going to let you all in on a little secret.

I’m a pretty good flier. No, my brain doesn’t accept the science behind how aircrafts stay in the air (I give it up to magic). No, I cannot quite turn off the part of my mind that thinks turbulence can take out an airplane (though, to be clear, it basically can’t). But, on the whole, I enjoy the absolute miracle that is being in the air enough, especially when we splurge for good seats and increased alcohol service, that I’m actually a pretty chill flyer.

Unless turbulence hits just right. Then I get vertigo and I am essentially a nightmare. Seriously, I get sweaty, I cannot stand up straight, all I want to do is be anywhere but a tight metal tube…

Suffice to say, I deeply related to Lithgow in this segment.

Again, we have a section of the film based on one of the most famous episodes of The Twilight Zone ever, maybe the most well-known segment the show ever did. Once again, I have The Simpsons to thank for my working knowledge of the major beats, although I am aware that the original episode starred William Shatner* as the airline passenger who starts losing his mind at the sight of a gremlin wreaking havoc on his flight’s wings, and oh man, if ever there was an actor who is built for the kind of paranoia-fueled performance this story demands, it’d be him.

*Shatner, by the way, is an actor who I think gets kind of a bad rap, thanks to decades of parodies and imitations that depict him as. Having. This. Staccato. Style. Of Speaking. But, if you actually watch an old episode of Star Trek or something, he doesn’t really sound like that at all? It’s a classic case of an exaggeration becoming the standard over the course of time.

But Lithgow does a pretty good job, too! I’m not a guy who thinks everything Lithgow does is good (I’ve mentioned it before, but he has that “fake British guy” energy that kind of grinds my gears sometimes), but his sweaty, shouty, claustrophobic freakout really worked for me here. I just kinda bought him as a dude who’s having the worst time; on top of being on a horrifically bumpy flight, I think if I saw a fucking gremlin out my window, I’d be as much of a blubbering mess as Lithgow is here.

The whole segment was probably my favorite for two other reasons. One, the gremlin is another triumph of handcrafted puppetry. It looks gloriously horrendous and tactile, in a way that would just never be achieved had the movie come out in 2025 (one can only imagine the CGI monstrosity we would get now). Two, George Miller’s masterful depiction of closed-in spaces, and the fear that arises from them, is as unshowy as it is unparalleled. He allows himself a flourish here and there (my favorite was a very quick cut of Lithgow with comically popped eyes during the initial reveal of the gremlin), but otherwise, he keeps it grounded and grimy here, making the airplane feel like some sort of horrifying tomb.

And, of course, Aykroyd’s quick cameo at the end as the ambulance driver (who appears to be the same guy in the prologue), brings the whole movie full circle in a way that seemingly tries to make you go, “hey, maybe you enjoyed the entire thing, instead of just the last fifty minutes”. It’s a trick TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE almost gets away with. But then, the credits for Landis’ portion comes up and you’re left with the same weird feeling you had an hour ago.

Overall, TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE is a wildly mixed bag, one that gives us a pair of great segments by two wonderful directors of the era, a really, really disappointingly inert segment by a director who should have been able to provide more, and a segment where three people were killed. What is one to make of an anthology film with such wild pendulum swings? Was there value in the movie being released at all? Maybe; again, the last two are really great. But the whole thing is infused with such noxious energy that it’s worth considering whether it would have been better for the movies to have just been chucked into the actual twilight zone, only to be stumbled upon by some poor fool needing to learn some ironic lesson.

Still, I really loved that scary rabbit puppet.

Can’t ALWAYS Nail It: Spielberg Summer 2 Concludes!

Spielberg Summer 2 wraps up with one of the more obscure entries in Steven’s filmography, the old-fashioned throwback ALWAYS. There’s a lot of love and sweetness to this movie, borne out of a mutual passion between star and director of a particular 40’s war film, but…ALWAYS just isn’t that great, mostly as a result of casting. Ah well, at least we get Audrey one more time.

When one reviews Steven Spielberg’s chronological filmography, 1989 stands out as a particularly significant year.

The end of the 80s provides us the first year to contain two Spielberg movies, although it certainly wouldn’t be the last: 1993 would yield both JURASSIC PARK and SCHINDLER’S LIST, 1997 would bring us THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK and AMISTAD, 2002 generated MINORITY REPORT and CATCH ME IF YOU CAN, 2005 was home to both WAR OF THE WORLDS and MUNICH and 2011 launched THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN and WAR HORSE. This quirk in Spielberg’s oeuvre is notable, both for how often it happened, as well as how these bespoke double feature almost always paired entries that were so different from each other, perhaps an indication as to his under-appreciated range in genre.

So it goes with 1989’s INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE and ALWAYS. The former was the latest (and temporarily final) entry in Spielberg’s throwback homage to the adventure serial, which ended up being a majorly successful endcap to his defining franchise. The latter was a passion project for both its director and its lead, borne both from the love of the same movie and a desire to pay tribute to the old-timey war pictures of the 1940’s. That one…well, that one was fairly less successful, both at the box office (74 million versus 474 million for INDY 3) and critically…well, at least in the eyes of this critic.

Let’s wrap up Spielberg Summer 2 with one of his more obscure works, the first without-a-doubt “one for me” film, one perhaps most remembered for it being a Hollywood legend’s swan song more than anything else ... .it's time for ALWAYS!

ALWAYS (1989)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, John Goodman, Brad Johnson, Audrey Hepburn

Written by: Jerry Belson, an uncredited Diane Thomas

Released: December 22, 1989

Length: 122 minutes

ALWAYS throws us into the world of aerial firefighting, as Pete Sandich (Dreyfuss) continuously shows off his propensity for flying recklessly into fires, unsettling both his best friend Al (Goodman) and his girlfriend Dorinda (Hunter). Over the course of the movie’s first hour, Dorinda finally gets Pete to hang up his wings and move into more of a mentor role in another town, to finally settle down and get married. Alas, before they do, Pete gets called in for one last job, and…well, you can probably guess what happens next.

As Pete awakes from the wreckage and finds himself now in the afterlife, he’s tasked with mentoring another young aerial firefighter, the brash Ted Baker (Johnson), a duty that goes awry when Ted ends up beginning to woo Dorinda. As Dorinda also begins to fall in love with Ted, Pete has to start asking himself, how long can he keep himself from moving on? At what point do you say in death what you never could in life, then allow the normal course of history to move forward?

It’s all very sweet in an old-fashioned way, which is completely by design. The impetus for ALWAYS getting made in the first place was Richard Dreyfuss and Steven Spielberg filming JAWS and bonding over a 1943 Dalton Trumbo-penned film called A GUY NAMED JOE. It turns out both men have an intense relationship with the movie, with Dreyfuss claiming to have seen it at least 35 times, and Spielberg crediting it as one of the films that inspired him to become a director in the first place (ever the lost child, he found a throughline between A GUY NAMED JOE and his own WWII veteran father).

So, the impulse to remake it makes all the sense in the world. More to the point, Spielberg had clearly reached the point of his career where he could start making movies that were purely “just for him”. He could have just as easily not made ALWAYS; it’s fairly definitively the least remembered film released during his prime years. Yes, it made 74 mill off of a 30 mill budget, and received some pretty decent reviews, all of which is preferable to being a public disaster like 1941. But after three INDIANA JONES movies, E.T. and major Oscar contenders like EMPIRE OF THE SUN and THE COLOR PURPLE (with major hitters like JURASSIC PARK and SCHINDLER’S LIST on the horizon) it’s odd that ALWAYS is just sitting there.

But it’s a movie about planes and WWII and (spiritually speaking) old Hollywood. It’s a project he got to work on with a cherished collaborator. So ALWAYS was made. Why not? It’s Steven Spielberg. And ALWAYS is a comfortable movie, both confident and competent in equal measures, and, when working through his filmography from start to finish, there’s admittedly something to be said for landing on such a small-feeling movie after a run of monumental blockbusters and awards fodder.

But, none of this really helps remove this basic fact…I didn’t like ALWAYS that much.

Yes, it’s a movie that gets accused of overt sentimentality (Leonard Maltin diagnosed it as having “a Case of the Cutes”, which, lol), and it’s not an incorrect criticism. But, even by 1989, we’ve basically reached a point in Spielberg’s career where that’s just kind of his thing. The cheese sometimes gets to be too much in ALWAYS, but I also went in expecting that. At the end of the day, it has its heart on its sleeve just as much as E.T., it’s just way more upfront about it.

No, my main issue with ALWAYS is that I just don’t buy the main romance, nor do I really buy Dreyfuss and Hunter together. I understand that Dreyfuss is kind of part and parcel with this project (it likely doesn’t exist without him), but he’s an odd fit for an everyman love interest role. What made his character work in Dreyfuss’ other Spielberg collaboration (JAWS) is that he was both the smartest guy in the room, and also fairly anti-social. Even when he was right about his assessment of things, it was fun to watch Quint laugh in his face and tell him to sit down. Dreyfuss is simply more effective when he’s high-strung. He’s not exactly ideal for a roguish flyboy who is humbled in the afterlife.

As for Holly Hunter, she’s just one of those “I’ll take your word for it” actresses for me; she’s never actively frustrated me, but I also feel alienated by those that adore her. I’ve always found her a little cold and distant, which can admittedly pay off in some roles. But in a sweeping old-fashioned romance? She just doesn’t work for me. Put Hunter and Dreyfuss together and you get a couple who sometimes seems shocked to be in the same room at the same time.

The problem is that ALWAYS absolutely hinges on you being invested in these two. The whole thing depends on it. And if you don’t…well, ALWAYS just kind of lies there, especially in its first hour, which is constantly laying the tracks for these two characters to reach their tragic separation, a move that you frankly can see coming a mile away. And that predictable plot doesn’t necessarily need to be a problem in a love story; it could even be a benefit in drama if done right. Consider that the play Romeo & Juliet opens with a prologue that tells us they’re going to die. Yet, in the hands of a pair of great actors with strong chemistry, this tip-off has you on the edge of your seat, begging for the finger of fate to point elsewhere, just this once.

But Pete and Dorinda, alas, are no Romeo and Juliet. You just don’t believe they’re in love, or at least I didn’t. One has to wonder if a complete casting change at the top would have gone a long into making ALWAYS special.

Hunter and Dreyfuss aren’t the only weird casting fits. Another odd casting choice is that of Brad Johnson as the dashing Ted Baker. Johnson was apparently a former Marlboro Man making his film debut, and he’s definitely fine, if unremarkable. But it’s the type of role that demands a star-level presence to justify the threat Pete feels towards him, as well as (again) to buy the blossoming romance between Ted and Dorinda. Baker just didn’t move the needle for me. Allegedly, at one point in the films’ decade-long development period, Ted was going to be played by Tom Cruise, which…hell yeah, 80’s era Cruise! Now we’re talking. I think if Cruise were able to tap into his charming and raw, in-need-of-mentoring persona from THE COLOR OF MONEY, I think that would have given ALWAYS the little extra boost it needed.

ALWAYS is not all bad. John Goodman is his normal fun self in the “best friend” role, and Marg Helgenberger briefly livens things up in a pair of scenes. But nothing can really overcome the fact that, for as near and dear to his heart this source material and filmmaking style is to him, Spielberg is kind of on auto-pilot here. The opportunity to see him cut his teeth on a smaller budget again, after a decade of skyrocketing fame, should have allowed him to infuse the screen with some passion and intimacy. Instead, ALWAYS often resembles an over-long episode of an anthology series.

Of course, the most famous thing about ALWAYS is the fact that it wound up containing the final film performance for one MS. Audrey Hepburn, a legend with a filmography that’s somewhat briefer than it might feel (27 movies in all, and a few of the early ones are really glorified bit parts). Yet, her career manages to speak for itself all the same: nobody can argue the legacy of a woman who starred in SABRINA, ROMAN HOLIDAY, FUNNY FACE, BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY’S, fucking CHARADE, MY FAIR LADY, HOW TO STEAL A MILLION and (one of my sneaky favorites of her career) WAIT UNTIL DARK. It’s a career worthy of a retrospective all its own (and in fact, in a previous iteration of this blog, I dedicated a whole month to her work). So it’s hard not to get swept up in the moment of her showing up on screen for the last time, chronologically speaking.

And, look, even at the age of 59, she has that undeniable, one-in-a-lifetime screen presence that elevates even the thinnest of roles, and there’s something kind of sweet about the idea of being greeted in heaven by Audrey Hepburn. But…if you remove all of that, it’s hard to square the fact that her role is…deeply strange? Like, who is she, really? Is she an angel? Is she God? Why is she giving Pete a haircut? It feels for all the world like the goal here was just to give this vague role to a Hollywood superstar and hope nobody asks any questions. It almost works, an indication of pitch-perfect casting.

Anyway, Audrey’s great in this, and she single-handedly provides some historical importance to ALWAYS (as well as a solid, definitive reason to watch it), a movie that otherwise might have faded away entirely. It’s not a disaster, and I’m not surprised by the occasional hot take online singing its virtues. However, you’re not likely to see one of them fired off by me.

That said, ALWAYS is a good example of this Spielberg Summer project’s appeal for me. There is a very real chance I would have had no other incentive to check this one out, and I was finally able to check this one off the list. There will eventually be no new Spielberg movie for me to finally see; thus, I may as well cherish the ALWAYSes of his filmography while I have them.

Anyway, that’s a wrap on Spielberg Summer 2. Next time we pick this project up, I’ll be diving into his 90’s output, including some of his biggest movies ever. I can’t wait! I hope you can’t either.

INDIANA JONES’ First LAST CRUSADE: Spielberg Summer 2 Continues!

This week, Spielberg’s signature franchise comes to its original close (even if the series would go on to drink from the cup of eternal life). INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE spends a little too much effort apologizing for TEMPLE OF DOOM, but makes up for it with an inspired crucial piece of casting and by…well, by being really fun and funny for two straight hours. Let’s ride off into the sunset together!

Back when I was a kid, when there were a meager three Indiana Jones movies, I had to reckon with a simple fact…

…I had always found myself a little bored with INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE.

In some ways, the movie never had a chance. I had seen RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK in an actual movie theater, and it was one of those formative moments for me as a blossoming movie guy. I had caught INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM sleeping over at a friend’s house as a kid, which turned out to be a delirious experience, especially having only seen RAIDERS up to that point; every scene seemed to be crazier than the last, but it was so late at night that the movie felt like it was somehow four hours long. If you had told me I had dreamed the whole thing, I likely would have believed you.

Finally, a couple of years after that, I procured a three-tape VHS collection of the entire Indiana Jones trilogy* and it was finally time to see the story capper, the third and final Indiana Jones tale, the absolute last one we’ll ever get (it’s in the title, after all!).

*Along with a bonus fourth tape containing an episode of the Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. I…never watched that one.

I put it on one night and watched it with my mom. And…I thought it was just okay! I didn’t hate it or anything, but, to be honest, I felt a little underwhelmed by it. Maybe it was because it felt a little too similar to the first one, maybe it’s because I watched it in the comfort of my own home instead of literally anywhere else, causing the moment to blend in with the infinite amount of times I had watched a movie on the family TV, but…LAST CRUSADE just didn’t stand out to me in any way, and it comfortably existed as my least favorite Indiana Jones movie.

Of course, it turns out you’re really stupid when you’re a kid. Returning to this one a couple of times over the past few years has revealed to me one of the more comfortable third entries in the history of franchise filmmaking, even as I still feel its active hesitance to do anything too alienating. Oh, and it’s also really, really funny. Like, easily the funniest of the five Indy films.

As we inch closer to the end of Spielberg Summer 2, let’s take one LAST CRUSADE with Indiana Jones this year!

INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE (1989)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Harrison Ford, Sean Connery, Julien Glover, Denholm Elliot, Alison Doody, John Rhys-Davies

Written by: Jeffrey Boam (screenplay), George Lucas & Menno Meyjes (story)

Released: May 24, 1989

Length: 126 minutes

This time, we catch up with everyone’s favorite archeologist in 1938, and this time, he’s on the case to find two treasures. First, he’s after the Holy Grail, the famous cup that Jesus drank from during the Last Supper. Second, and more importantly, he’s also on the hunt for Henry Jones Sr., his father who has gone missing during his own pursuit for the Grail. Along the way, Indiana Jones will meet back up with old friends like Marcus Brody and Sallah, as well as face new adversaries, like the treacherous Elsa Schneider, the Nazi-sympathizing Walter Donovan, and maybe…just maybe…Adolf Hitler himself. What a fitting last crusade this is shaping up to be!

As alluded to in the intro, there’s a strong element of apology weaved into LAST CRUSADE’s fabric in the wake of the controversy surrounding the darker and more violent content of TEMPLE OF DOOM five years prior, with as many references and structural similarities to RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK thrown in as it could fit. Indiana Jones teaching a classroom full of love-smitten girls*! An adventure to recover a crucial Christian architect! The return of Marcus Brody! The return of Sallah! The return of Marion Ravenwood….iiiinn the next one! Hell, they even bring back that famous “moving thick red line on a map to indicate the characters are traveling!” thing that was missing from the last one.

*And, to my eyes, at least one male? Don’t get me wrong, I get it. I was just surprised, is all.

In many ways, there’s a logic to this mea culpa philosophy, a line of thinking that can best be described by the “Sorry. Im sorry. Im trying to remove it” dril tweet. TEMPLE OF DOOM has a more-or-less redeemed reputation nowadays, and it did make a ton of money (although, crucially, less than both RAIDERS and LAST CRUSADE), but it was also at the center of a firestorm regarding the content in movies “these days” and basically kicked off the PG-13 era of Hollywood. I get that, now that Spielberg and Lucas were in better head spaces at the end of the decade, there would be a desire to go back to what worked.

In other ways, though, this has always made me feel bad for LAST CRUSADE. I don’t like when movie franchises feel the need to apologize for big swings taken by previous installments*, if only because it always comes off a little desperate. Movie sequels do this kind of thing all the time, burning valuable screen time evoking the original movie (the most egregious example is Jack Sparrow’s very first line in the second PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN, a hamfisted redo of the “why is the rum gone” joke that everyone liked in the initial film). I never like it! TEMPLE OF DOOM is easily my least favorite of the first three Indy movies, but that’s only because of a crucial failure in casting, not because of its shift in tone and mood. Redirecting in the face of controversy would suck some of the ambition out of the Indiana Jones franchise from then on (although Four and Five would admittedly take some big swings of its own; aliens and time travel, anybody?).

*It should be noted, though, that viewed through this prism and this prism only, the original three INDIANA JONES movies resemble the philosophical arc of the STAR WARS sequel trilogy: an initial movie that makes a big splash, a follow-up that goes in a completely different direction, followed by an endcap that tries to resemble the first movie as much as possible under threat of execution.

It even feels like it’s apologizing for TEMPLE OF DOOM’s refusal to act like a proper prequel. This time, LAST CRUSADE does that “long-running franchise” thing of going back to the past and showing us how our main character became who he is, the main pitfall TEMPLE OF DOOM avoided for the most part. We get an extended prologue of young Indiana Jones (played by 19 year old River Phoenix!) on his first little adventure, gaining his famous hat and fear of snakes along the way. By all accounts, this is a sequence that should cause major eyerolls for me, it standing for everything I find very exhausting about sequels and all.

But…I kind of like it. I mean, yes, finally learning how Indiana Jones got his fucking hat* is of no interest to me and never will be, but I think this opening chapter is actually quite fun, full of energy, full of that patented Spielberg-ian storytelling-through-action style. Yes, all that “oh, he’s using the whip for the first time!” stuff is there if that’s what you’re interested in, but the whole thing is really more in service of establishing something that hadn’t even been hinted at in this series up to this point: Jones’ relationship with his father. Speaking of….

*It turns out…someone gave it to him. Whoah!

I feel like I’m in no real danger of putting too fine a point on this next statement: Sean Connery as Indiana’s father is one of the most inspired pieces of casting in the entire franchise. He fits into the series so well, to the point where it’s hard to imagine any Indiana Jones movie without him (although most of them don’t). Connery was in an interesting period of his career, having recently come out of a two-year exile after the production frustrations with his off-the-books James Bond comeback, 1983’s NEVER SAY NEVER AGAIN. He was riding the wave of films like HIGHLANDER and THE UNTOUCHABLES, the latter of which earned him a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. It seemed the perfect time for Spielberg to get as close to a life-long dream (directing a Bond film) as he will likely ever get; directing the guy who defined the role for many generations.

He’s so fucking good in this. I dunno. It’s hard to put it in any other words than that. He’s warm and funny where he needs to be, vulnerable in other moments and, most importantly, is able to exactly equal Harrison Ford in screen presence without ever upstaging him. It’s a remarkably comfortable performance from someone who would sometimes be unwilling to give his best towards the end (compare him in this to something like LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN, where he is providing third-rate material a performance it deserves). Hell, one of the funnier lines in the movie (“She talks in her sleep”) was apparently an ad-lib from Connery himself, a testament to how open he was to being playful with this role.

Speaking of funny lines and moments, I think the most remarkable thing about LAST CRUSADE is how funny it really is. I suspect this was a conscious choice, a further attempt at distancing itself from TEMPLE OF DOOM. But, it’s one thing to decide to be light and funny, it’s a whole other thing to actually achieve it. LAST CRUSADE contains two whole scoops of bits and business, and they pretty much all work. Henry Sr. accidentally shooting the airplane tail. Harrison Ford doing a fucking Scottish accent. Indiana ending up with a genuine autograph from Hitler himself. My two favorite moments, though, consists of one I had always remembered, and one that I hadn’t.

One I remembered: as Henry and son end up in the clutches of the Nazis, there is this beautiful build-up from (and zoom-in on) Indy about how Marcus Brody, intrepid and loyal friend, is in custody of the diary pages they seek, how he’s too far ahead of them, too connected, too smooth, too familiar with any and all local customs, and will be able to disappear before the Nazis ever know what’s happening. The cut to Brody lost in the streets of Alexandretta, just kind of wandering around, is maybe the funniest moment in a Spielberg movie.

One that I hadn’t: there’s a moment where Indy and Henry are being chased through an airport. As we watch their assailants run through the station, we eventually pan over to two people rather conspicuously holding up newspapers in front of their faces. “Aha! That old trick”, we think to ourselves. As they run by, we assume Indy and Henry are now in the clear. And they are; the reason we know this is because they emerge from the staircase behind these two newspaper guys, who end up really just being two guys reading newspapers! It’s such a dumb joke, but it’s also so delightfully playful.

I think this willing levity is why LAST CRUSADE is able to get away with stuff that normally grates me when they appear in other films. Yes, it’s trying to get the taste of the last one out of its mouth, and yes, it provides hamfisted lore drops* because that’s just what you do in a franchise. But (and this is crucial), it’s done in the spirit of fun, as opposed to abject reverence towards the property. It’s not trying to deify the character of Indiana Jones, it just wants people to have fun with him again.

*Another one that makes me kind of roll my eyes….Indiana Jones’ dad is scared of rats. This is in juxtaposition, you see, to Indiana Jones’ famous phobia of snakes. LOL!

And, as it happens, LAST CRUSADE is a lot of fun! Mission accomplished there. Of course, there’s something a little deflating about watching a movie called LAST CRUSADE, with a story that is already lightly hinting at the idea of Indiana Jones hanging up the whip (an early scene has a villain implying that he is the one that belongs in a museum now), one that ends with Jones riding into the sunset, the ultimate hero’s ending, and remembering “oh yeah, there’s two more of these now”. You do wonder if the 21st century has sapped some of this film’s power, now that it is no longer a series capper, but instead a midpoint.

I understand the constant temptation to return to the well when it comes to successful film franchises, and although we’ll talk about INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL in this space two years from now, I feel like it’s worth mentioning that I thought INDIANA JONES AND THE DIAL OF DESTINY was a good-enough “official finale” for the series. But I’ve always felt like Lucasfilm has forgotten the lesson Indy learns at the end of INDIANA JONES’ first finale…

…his quest for the Grail leads to him “choosing….wisely” and drinking from the chalice, granting him immortality. Immortality, of course, comes at a price, as the Grail’s current keeper informs him. Once he leaves the confines of the temple in which it resides, he will be immortal no more. His only task he can have as an unkillable being is to stay in this one room, keeping watch over the Grail. Obviously, a life with no end that comes with such restrictions is no life at all. Jones chooses to take off into the sunset with his father and friends instead.

At least the character does. His eponymous movie franchise, on the other hand, appears to have chosen to stay inside the temple, keeping guard over a property and extending its life into the infinite. It’s too bad. Had the INDIANA JONES series enjoyed its mortal life, the last image of him riding into the sunset might have been the perfect note to go out on.

But, you can’t always stop the keepers of a billion dollar franchise from choosing…poorly.

Steven Comes of Age With EMPIRE OF THE SUN: Spielberg Summer 2 Continues

A bit of a forgotten entry in Steven Spielberg’s 80’s filmography, EMPIRE OF THE SUN is still a worthy viewing due to its gorgeous visuals, insightful script, and a great central child performance, from an actor I don’t usually even like that much! So, why doesn’t it have the same clout as some of Spielberg’s other films? It may be a matter of timing.

For most people, childhood is a silo.

An adult raising a child has many jobs, but one of the most important ones that come up over and over again is the protection from the harsh reality of the world surrounding them. I was a 90’s kid, growing up in a decade that is being looked back on lately with rose-colored glasses by essentially every single person my age. This is in spite of several turbulent events: the Columbine school shooting, the killing of Matthew Shepard, the impeachment of the President of the United States, the tumultuous murder trial of a famous football player, riots in Los Angeles, the bombing of a federal building…and that’s just keeping the focus on things stateside.

But I didn’t really care, and truly barely knew, about any of it at the time. I was too busy reading Calvin & Hobbes and watching Animaniacs and drawing shitty pictures, as a child is supposed to do. Pretty much all of my peers were. We had our own internal battles to fight, to be sure, but we were siloed from the horrors of the outside world, even in a (relatively) stable era.

Of course, that loss of innocence, that “coming-of-age” moment, when the silo breaks and the outside world finally leaks in, that moment arrives and you’ve now been altered forever (for most of us, that was probably September 11th, 2001). Unless you’re overwhelmingly lucky, it’s a period of life that is usually inevitable, and it’s ultimately a necessary one. Coming to terms with the fact that the world can be arbitrarily cruel, that sometimes people just suffer, that your parents aren’t always going to be there to help you swim through the murky waters of the chaos….it’s painful, but it’s needed.

Those types of moments in life tend to form the backbone of most Steven Spielberg movies; it’s no accident they often feature kids separated from their parents. The universality of those periods of life allows it to be applied to just about any kind of setting: 1930’s Cairo, 70’s Middle America, the far distant future, a theme park filled with dinosaurs…this period makes any imaginable world instantly recognizable, because we all go through it.

Of course, because of this, the exploration of this crucial chapter in everyone’s life served Spielberg well when he returned to the historical time period that captivated him as a young lad, barreling towards his own silo-bursting: World War II.

EMPIRE OF THE SUN (1987)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Christian Bale, John Malkovich, Miranda Richardson, Joe Pantoliano

Written by: Tom Stoppard

Released: December 11, 1987

Length: 154 minutes

EMPIRE OF THE SUN tells the story of Jamie Graham (Bale), a British schoolboy living a very posh, and extremely privileged life within the Shanghai International Settlement in the early 1940’s. This cushy existence is maintained even as World War II rages on in the background, and Japan continues to ratchet up its invasion into China. The bubble gets forever burst once Japan attacks Pearl Harbor and the Pacific War officially begins. As people begin to evacuate, Jamie is separated from his parents and this upper-crust kid is now left to figure out how to navigate an uncertain world on his own. As the movie goes along, and Jamie finds a kind of bespoke father figure in a thief known as Basie (Malkovich), the question becomes: what kind of man will Jamie be?

The first thing about this I wanted to mention: my knowledge of history is weak enough that I always love it when a movie teaches me about something that I ought to have known about already. I had no idea about the Shanghai International Settlement, nor that it existed for as long as it did (first established in 1863!). Whenever something from world history gets depicted in a major film, I automatically assume that everybody else just already knew about it. However, if you didn’t know about this particular piece of it…well, hey, you oughta check out EMPIRE OF THE SUN!

The second thing to mention: EMPIRE OF THE SUN was initially conceived as a possible David Lean picture! Yes, after original choice Harold Becker dropped out of the project, Lean was brought in to adapt the J.G. Ballard novel, with Spielberg producing. However, Lean just never developed a connection to the material, and he eventually passed the project along to Spielberg, who secretly wanted to direct it all along. And, look, you can definitely see a lot of Lean in this visually (and that’s probably no accident; Spielberg is an avowed fan, citing BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI as one of his favorites of all time). At the end of the day, though, EMPIRE OF THE SUN is unmistakenly a Spielberg movie. We’ve got lost children, found fathers, World War II, a reverence for aviation, swelling music…you couldn’t miss his fingerprints on this picture if you tried. E.T. was definitely his “divorce movie” up to this point, but you can’t help but feel like he heavily reflected on the separation of his parents when reading the novel.

These Spielbergian hallmarks also help make EMPIRE OF THE SUN feel kind of comfortable in its own little way, at least in the way it communicates its story and themes. The set up for Jamie Graham, the character in which we view the entirety of the film’s events, is particularly satisfying. As mentioned, he’s a boy who’s been placed inside a bubble, both functionally and metaphorically, by virtue of living within the confines of the Shanghai settlements. To him, the biggest issue he faces is whether the maid will allow him to have his favorite buttered biscuits before bed or not. He lives wrapped up completely in a cloak of privilege he (understandably) has no awareness of*. This is exemplified perfectly by the Graham family’s early trip to a lavish party across the city. The commute to the party leads them through a chaotic and overcrowded Shanghai street. Pressed faces, hustling children, bloody food wares streak across the passenger side window. They’re right there, right in Jamie’s face, yet cannot touch them. He can observe them, but he’s not affected by them.

*Although not from lack of trying by his parents. His dad reminds Jamie in the beginning, who becomes fixated on a homeless guy right behind their wall that they have more luck than most, and the homeless guy still has more luck than some. It’s a nice moment of humanity from a character that could have been really nasty.

EMPIRE OF THE SUN continues the exploration of the role of a father that THE COLOR PURPLE began. Once Jamie is separated from his actual dad, the movie involves Jamie trying to find new parental figures to latch onto, and boy, does he find a complicated one in Basie. He’s a transient sailor, a thief and an opportunist in every sense of the word. Although Basie is comfortable having Jamie tag along once they happen to cross paths (via his compatriot Frank, played by Joe Pantoliano), he also makes it very clear through his actions that he will bail on this orphaned kid if he feels like he needs to. Hell, on the first day they meet, Basie gives a good try to sell Jamie off to some strangers. This makes for an interesting turn when the two of them (plus Frank) end up rounded up by the Japanese, into a holding center, officially hostages of a foreign government.

In the hands of Malkovich, Basie becomes a great piece of the thematic bricks that EMPIRE is built off of. He’s the type of adult you tend to meet over and over again once your world expands beyond the confines of your own home. As it turns out, many human beings end up existing for themselves, even when they turn out to have something of value to teach another person. Jamie does pick up some legitimate street smarts from the guy, which is invaluable for his survival (and, in some cases, even thriving) in the camps. However, this sort of mentorship doesn’t actually translate into any sort of love. In one of the more heart-breaking moments of EMPIRE OF THE SUN, Basie gets selected by the Japanese to be transferred from the holding center to an official camp. Despite his loud pleas to be brought along, Basie puts his head down as he climbs into the truck and pretends not to notice. The Tom Stoppard-penned script can’t help but twist the knife here: Jamie ends up also getting chosen to be transferred, and they both have to sit there in that truck, knowing how Basie really feels.

That is the purpose of a “coming-of-age” story, though, that change from a child to something resembling an adult, and there’s no more profound moment in life than realizing that, oftentimes, you’re on your own. So it goes for Jamie: the only reason he gets chosen for transfer is by annoying his way onto the truck, pestering the driver into letting him give more appropriate directions to where they’re headed. In a moment of crisis, he’s now proven to be self-reliant. Perhaps he’s grown beyond Basie entirely.

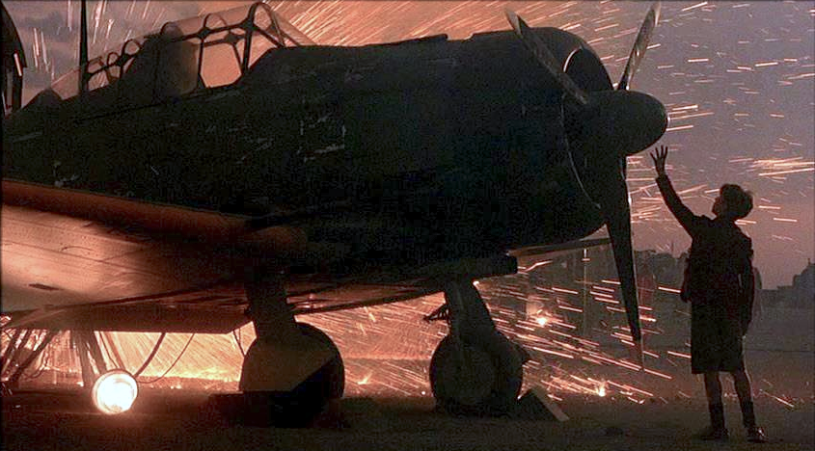

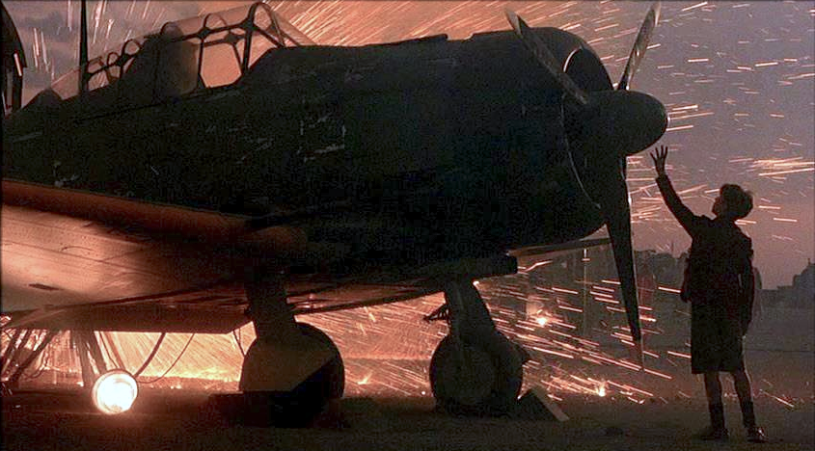

I should point out here that, yes, EMPIRE OF THE SUN details a very harrowing and grueling story, involving a lost child forced to grow up in the crucible of government occupation and captivity. But Spielberg’s direction does keep things from feeling too heavy, often to the film’s benefit. There is a fair amount of whimsy throughout, best exemplified by a scene halfway through (in some ways, it feels like an Act One finale). Something that we know about Jamie consistently throughout the story is his obsession with the act of flight and the craft of an airplane (another way the director is undoubtedly infusing himself into this tale). An early moment involves him sitting in the cockpit of a long-since-wrecked plane, imagining himself as the hero of one of his beloved magazines. At one point during his tenure in the Japanese holding cell, however, he stumbles across a team of pilots fixing up a fleet of fighter jets. The sparks of the soldering irons feel something like fireworks, as Jamie becomes captivated, seeing an airplane in person for the first time. Although he gets yelled at by a general to get back, the pilots seem a little more amenable; as Jamie salutes in reverence, and the John Williams score swells*, they salute back. As it turns out, nothing can bring two enemies together like a shared love and interest.

*You’ll never believe it, but John Williams did the score to this Steven Spielberg movie.

Yes, I know that Spielberg’s handling of darker materials at this stage of his career is something that has been questioned, but I maintain that moments like this work really well, possibly because it’s a story being told from the perspective of a twelve-year old, as opposed to an adult. That said, Spielberg does, alas, push the whimsy just a tad too far at places. There’s a moment in EMPIRE OF THE SUN that, had it been written as a vicious Spielberg parody, would have had not a single syllable altered. Late in the film, Jamie watches as an ailing fellow prisoner, Mrs. Victor (Richardson), passes away in the middle of the desert. As she dies, we suddenly see the fallout of the Nagasaki bombing off in the distance. Jamie, in his childlike innocence, believes the fallout to be Mrs. Victor’s soul flying away to heaven. Woof.

Still, the film gets away with these saccharine moments, because the performance at its center is so good. Take it from me: I am a fairly avowed Christian Bale skeptic. He’s not the most irritating actor on my enemy list; he actually has a handful of adult performances that I think are pretty good (I think the “Batman voice” meme has overshadowed just how strong his Bruce Wayne is in the Nolan DARK KNIGHT trilogy!). However, he’s one of those guys who has a whole “method acting” hype machine behind me that makes any potential criticism of his work instantly invalid in the eyes of many a fan, in both online and real life spaces. “How can you say Christian Bale isn’t a great actor? Didn’t you see how much weight he lost for THE MACHINIST?” “How can you say he’s overrated? Don’t you know how seriously he takes his roles, even in shit like TERMINATOR 4?” Cool! Good for him! I never realized that acting could be quantified by the amount of interesting behind-the-scenes facts you can regurgitate about someone*. Here I thought I was just alienated by most of his work. I’ve seen the light!

*You absolutely do not want to start the Daniel Day-Lewis conversation with me here.

ANYWAY, that said, imagine my surprise when I found his lead performance here, at the age of 13, to be easily the best thing I’ve ever seen him do. Jamie is an enormous role that requires a lot of emotional range, coupled with the normal pitfalls that come with hinging the success of your entire film on the shoulders of a child. In this sense, Bale is great. In the beginning, he’s entitled without being annoying. By the end, he’s confident without being precocious. He has a remarkable amount of self-control, considering, again, he’s a teenager. I truly, truly kept waiting for him to piss me off. It never happened. One can only imagine what his performance would have been like if he had known to gain thirty pounds first.

Putting EMPIRE OF THE SUN in context with his complete filmography, it becomes clear why it’s become the ultimate “underseen and underrated” Spielberg film. Despite its relative high quality, it’s flanked by too many all-time Hollywood classics: RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK. E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTIAL. The one-two punch of SCHINDLER’S LIST and JURASSIC PARK a few years later. It just never hit the zeitgeist the way many other Spielberg movies did. Although it earned six Oscar nominations, they were all in technical categories, and resulted in zero wins. EMPIRE OF THE SUN probably just got overshadowed by another big historical epic from a legendary director that year: Bertolucci’s THE LAST EMPEROR. Hell, even the name is pretty similar.

It’s also not one of his very best. But I do think, were you to watch it, it would become an easy answer for you the next time someone asks you for a film recommendation. If nothing else, it makes you reflect on the way we ultimately have to navigate a sometimes-scary world, how to navigate trusting another person, how to grow into yourself, how to connect with the things you love, even when gatekept by an enemy.

Oh, and a young Ben Stiller somehow appears in this very briefly. That definitely makes for a fun fact at a trivia night, if nothing else.

Steven Grows Up With THE COLOR PURPLE: Spielberg Summer 2 Continues!

This week, Steven Spielberg begins to expand his directorial palette with 1985’s THE COLOR PURPLE, a sweeping literary adaptation featuring many great performances, and an ever-growing master behind the camera. However, it’s ever fascinating for the moments where you catch Spielberg being unsure with how best to depict serious stories of human misery. Yes, it begs the question: was he the right person for the job? But one also has to ask: without this, does Spielberg become the director we know him to be today?

I often find myself struggling with movies about human misery.

For a couple of reasons, I hesitate to make reference to “message movies”, as these types of films are often called. For one, I kind of think all movies are “message movies”; what is a film if not an artist communicating with people, even if what they’re trying to communicate is “seeing hot people try to defuse a bomb is cool” (in the case of Jan de Bont’s SPEED) or “I’m a fucking freak” (in the case of Dan Aykroyd’s NOTHING BUT TROUBLE). But for two, the term “message movie” has always felt pejorative to me, the unspoken implication being “a movie is trying to open my mind to something, oh no!” That said, there’s no precisely correct way to teach an audience anything, and I think the pitfalls to getting it wrong is what causes some people to get bumped, including myself.

There appears to be two main ways a movie teaches us about human misery. It can go for a glossy Hollywood style, where emotions are cued with swelling & active scores, and the screenplay lands itself on some kind of inspiring, if not precisely happy, conclusion. The tradeoff with this style is that you’re still providing the audience their most common aim of watching a movie in the first place (to get swept away from reality for a while) without risking alienation, but are not precisely providing…well, reality, defeating the purpose of the intense subject matter in the first place. So, you can instead go for stark, relatively uncompromising realism. In that method, you remain blunt and truthful, but at the risk of closing yourself off from wide swaths of potential ticket-holders (not everyone feels like watching something that bleak).

In THE COLOR PURPLE, you feel a movie that seems to be vacillating between both styles, unsure of how to exactly find the marriage between the two. And I suspect this may be because Steven Spielberg himself was aiming to go for the second style, while ultimately feeling more comfortable with the first.

It makes for a fascinating, not wholly bad, viewing experience. We’ve reached a Spielberg movie I had never seen! Always exciting. Let’s talk a little COLOR PURPLE!

THE COLOR PURPLE

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover, Margaret Avery, Adolph Ceasar, Rae Dawn Chong

Written by: Menno Meyjes

Released: December 18th, 1985

Length: 154 minutes

Adapted from the 1982 Alice Walker novel of the same time, THE COLOR PURPLE tells the epic story of Celie Harris-Johnson, a woman born into a horrifying world; by the time she’s a teenager, she’s already lost two children fathered by her dad. Not long after, she’s married off by the same dad to another abuser, a man known as “Mister”. The only shining light in Celie’s life is her younger sister, Nettie. Seeking refuge from their dad, Nettie ends up living with Celie and Mister, an arrangement that collapses after Nettie refuses to let him rape her. From there, it becomes a film-long quest for Nettie and Celie’s paths to hopefully once again unite.

THE COLOR PURPLE is a real fun time, as you can see. However, it should be said that, although the subject matter remains serious throughout, there are many moments of life. And light. There’s song and dance and genuine displays of love (and, yes, the color purple), just like there is in even the darkest parts of lives. But the dark realities of Celie’s life, as it is for so many of those in marginalized communities, both then and now, always seem to boil back to the surface.

The cast is interesting, especially considering its lead is someone we don’t really associate with drama these days. This was more or less Whoopi Goldberg’s screen debut*, and she’s done serious roles over the decades, for sure. But I’m guessing most people my age associate her as one of the rotating Oscars hosts in the 90’s and 00’s, or as one of the hosts of THE VIEW, which has made her a regular source for dumb culture war controversy (not helped by her penchant for making statements that don’t always make a lot of sense).

*Unless one counts William Farley’s 1982 indie flick CITIZEN: I’M NOT LOSING MY MIND, I’M GIVING IT AWAY.

Anyway, she’s pretty good in this, and is putting in the type of performance whose power doesn’t really hit you until after you’ve watched the movie and sat with it for a few days. It’s a performance fueled by repression, which means it’s robbed of the ability to be showy, like others in the movie get to be. But Goldberg doesn’t need to be showy here anyway; she’s able to absorb the series of blows that Celie’s life takes and is able to get us to track her emotions even when she’s silent. It’s the type of performance in the type of high-profile performances that practically guarantees someone an Oscar nomination (and, lo, she was).

I had two other standouts. For one, Danny Glover does an incredible job with a difficult role. Mister is one of those characters who is, for 97% of the runtime, just a bottom-of-the-barrel scumbag, not so much wanting a wife as a slave, all the while openly lusting after another woman, Shug Avery, the proverbial One That Got Away. He’s miserable all the way through. There’s a very real risk of a character like this serving nothing but a stone over the neck of the movie; can you really watch a guy traumatizing everyone around him for two and a half hours?

But, Glover is successful in making him seem…almost charming at first! To be clear, there’s nothing charming about the system of marriage as depicted in the movie (guy walks up to another guy and says “I wanna marry your daughter”, thus opening up formal negotiations). But there’s just enough of normalcy about him, even a nice smile, at the beginning that you trick yourself into thinking this may work out for Celie. Crucially, you also buy why a woman as self-assured as Shug might bother wrapping him around her finger for as long as she does.

I was also really taken by, of all people, Oprah Winfrey! She’s been known my entire lifetime as this person that’s just always been…around, first as a television personality (there appeared to be some unwritten, but fully abided, law in the 90s and 00s that at least one TV set in every American suburban household had to have The Oprah Winfrey Show on, even if nobody was actively paying attention to it), then as this figure people get either aggressively defensive, or aggressive, about. Oh, and I suppose she’s responsible for platforming a half dozen of the biggest dipshits to ever live, one of which is currently in charge of your parents’ healthcare. But…um…it’s easy to forget she has something like a dozen genuine film roles as well! That’s pretty cool!