Recent Articles

Steven Grows Up With THE COLOR PURPLE: Spielberg Summer 2 Continues!

This week, Steven Spielberg begins to expand his directorial palette with 1985’s THE COLOR PURPLE, a sweeping literary adaptation featuring many great performances, and an ever-growing master behind the camera. However, it’s ever fascinating for the moments where you catch Spielberg being unsure with how best to depict serious stories of human misery. Yes, it begs the question: was he the right person for the job? But one also has to ask: without this, does Spielberg become the director we know him to be today?

I often find myself struggling with movies about human misery.

For a couple of reasons, I hesitate to make reference to “message movies”, as these types of films are often called. For one, I kind of think all movies are “message movies”; what is a film if not an artist communicating with people, even if what they’re trying to communicate is “seeing hot people try to defuse a bomb is cool” (in the case of Jan de Bont’s SPEED) or “I’m a fucking freak” (in the case of Dan Aykroyd’s NOTHING BUT TROUBLE). But for two, the term “message movie” has always felt pejorative to me, the unspoken implication being “a movie is trying to open my mind to something, oh no!” That said, there’s no precisely correct way to teach an audience anything, and I think the pitfalls to getting it wrong is what causes some people to get bumped, including myself.

There appears to be two main ways a movie teaches us about human misery. It can go for a glossy Hollywood style, where emotions are cued with swelling & active scores, and the screenplay lands itself on some kind of inspiring, if not precisely happy, conclusion. The tradeoff with this style is that you’re still providing the audience their most common aim of watching a movie in the first place (to get swept away from reality for a while) without risking alienation, but are not precisely providing…well, reality, defeating the purpose of the intense subject matter in the first place. So, you can instead go for stark, relatively uncompromising realism. In that method, you remain blunt and truthful, but at the risk of closing yourself off from wide swaths of potential ticket-holders (not everyone feels like watching something that bleak).

In THE COLOR PURPLE, you feel a movie that seems to be vacillating between both styles, unsure of how to exactly find the marriage between the two. And I suspect this may be because Steven Spielberg himself was aiming to go for the second style, while ultimately feeling more comfortable with the first.

It makes for a fascinating, not wholly bad, viewing experience. We’ve reached a Spielberg movie I had never seen! Always exciting. Let’s talk a little COLOR PURPLE!

THE COLOR PURPLE

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover, Margaret Avery, Adolph Ceasar, Rae Dawn Chong

Written by: Menno Meyjes

Released: December 18th, 1985

Length: 154 minutes

Adapted from the 1982 Alice Walker novel of the same time, THE COLOR PURPLE tells the epic story of Celie Harris-Johnson, a woman born into a horrifying world; by the time she’s a teenager, she’s already lost two children fathered by her dad. Not long after, she’s married off by the same dad to another abuser, a man known as “Mister”. The only shining light in Celie’s life is her younger sister, Nettie. Seeking refuge from their dad, Nettie ends up living with Celie and Mister, an arrangement that collapses after Nettie refuses to let him rape her. From there, it becomes a film-long quest for Nettie and Celie’s paths to hopefully once again unite.

THE COLOR PURPLE is a real fun time, as you can see. However, it should be said that, although the subject matter remains serious throughout, there are many moments of life. And light. There’s song and dance and genuine displays of love (and, yes, the color purple), just like there is in even the darkest parts of lives. But the dark realities of Celie’s life, as it is for so many of those in marginalized communities, both then and now, always seem to boil back to the surface.

The cast is interesting, especially considering its lead is someone we don’t really associate with drama these days. This was more or less Whoopi Goldberg’s screen debut*, and she’s done serious roles over the decades, for sure. But I’m guessing most people my age associate her as one of the rotating Oscars hosts in the 90’s and 00’s, or as one of the hosts of THE VIEW, which has made her a regular source for dumb culture war controversy (not helped by her penchant for making statements that don’t always make a lot of sense).

*Unless one counts William Farley’s 1982 indie flick CITIZEN: I’M NOT LOSING MY MIND, I’M GIVING IT AWAY.

Anyway, she’s pretty good in this, and is putting in the type of performance whose power doesn’t really hit you until after you’ve watched the movie and sat with it for a few days. It’s a performance fueled by repression, which means it’s robbed of the ability to be showy, like others in the movie get to be. But Goldberg doesn’t need to be showy here anyway; she’s able to absorb the series of blows that Celie’s life takes and is able to get us to track her emotions even when she’s silent. It’s the type of performance in the type of high-profile performances that practically guarantees someone an Oscar nomination (and, lo, she was).

I had two other standouts. For one, Danny Glover does an incredible job with a difficult role. Mister is one of those characters who is, for 97% of the runtime, just a bottom-of-the-barrel scumbag, not so much wanting a wife as a slave, all the while openly lusting after another woman, Shug Avery, the proverbial One That Got Away. He’s miserable all the way through. There’s a very real risk of a character like this serving nothing but a stone over the neck of the movie; can you really watch a guy traumatizing everyone around him for two and a half hours?

But, Glover is successful in making him seem…almost charming at first! To be clear, there’s nothing charming about the system of marriage as depicted in the movie (guy walks up to another guy and says “I wanna marry your daughter”, thus opening up formal negotiations). But there’s just enough of normalcy about him, even a nice smile, at the beginning that you trick yourself into thinking this may work out for Celie. Crucially, you also buy why a woman as self-assured as Shug might bother wrapping him around her finger for as long as she does.

I was also really taken by, of all people, Oprah Winfrey! She’s been known my entire lifetime as this person that’s just always been…around, first as a television personality (there appeared to be some unwritten, but fully abided, law in the 90s and 00s that at least one TV set in every American suburban household had to have The Oprah Winfrey Show on, even if nobody was actively paying attention to it), then as this figure people get either aggressively defensive, or aggressive, about. Oh, and I suppose she’s responsible for platforming a half dozen of the biggest dipshits to ever live, one of which is currently in charge of your parents’ healthcare. But…um…it’s easy to forget she has something like a dozen genuine film roles as well! That’s pretty cool!

This was also her film debut and I think she probably gets the splashiest role, and arc, as Sofia. She gets to play a steadfast, confident woman in the beginning, with some genuine comic moments (one of the funniest moments in a movie designed to not have many involves everyone realizing she’s about to beat the shit out of someone at the jook joint), and then we go through the brutal process of seeing that confidence and independence stripped away from her, never to be returned, in the hands of white people both actively brutal, and self-assuredly “helpful” (more on Mrs. Millie in a bit). Much like Glover, Oprah does a striking job selling us on both ends of Sofia. By the time we reach the end, when she’s become this physically and spiritually beaten husk, you just want to crawl into a hole somewhere.

There are a lot of interesting thematic elements to THE COLOR PURPLE, the most compelling one being that of the role of a father. Shug (Margaret Avery) insists at one point that the best thing for a child is to have both a mother and father in the household. This is in spite of all evidence to the contrary displayed throughout the movie; Celie’s father is maybe the biggest monster in the whole story, kicking off a lifetime of trauma for her and Nettie. Mister is a miserable and inattentive father himself; all of his children grow up to be lost and immature adults. Through the prism of fatherhood, we even get some insight into what made Mister the way he is. His dad (played by the great Adolph Caesar) enters the story from time to time and is brutally honest with his son, in his own unique way that is neither precisely honest nor helpful. He recognizes the nasty qualities that Mister now displays in his adult life, but isn’t able to fully diagnose it, implying the women around him are to blame. One has to wonder how much better the world of THE COLOR PURPLE might have been had we been able to fully test Shug’s theory.

Another element that may take some who haven’t seen the movie or the book by surprise: the monsters and villains in this movie about Black pain are not just an interchangeable roster of racist white folk. (Some of the scariest people in this movie are, in fact, Black men, a fact that would earn it a good degree of controversy and, perhaps, cost it even a single Oscar win). That said, there are deeply racist white people in this movie, but the one that sticks out in my mind as the most sinister is Miss Millie, the wife of the mayor that attempts to hire Sofia on as a maid. She sticks in my craw so intensely because she’s a white character that, in her mind, is being helpful! She’s giving this poor colored woman a job (as if she had asked in the first place). Even though Sofia refuses, Miss Millie ends up getting her way; Sofia’ refusal gets her beaten by a mob and arrested. When she’s finally released, it’s into the custody of…Miss Millie, who’s delighted to now have someone who can teach her to drive. She commoditizes a Black body to feel better about herself. It’s a profoundly evil character, and she doesn’t even know how evil she is.

I do think Miss Millie is representative of Spielberg’s discomfort with some of the material. Millie is given some weird comic material to play; her aforementioned inability to drive causes crowds to start bolting when she hops into a car, which is funny. But it’s a broader joke that we see anywhere else in THE COLOR PURPLE (and plays out in juxtaposition to a concurrent serious moment), perhaps an attempt by Spielberg and screenwriter Meyjes to find the audience some comic relief. It’s a good instinct, but it’s acted on in an uncomfortable way.

Spielberg’s discomfort comes out in other, more active ways. One of the biggest blunders Spielberg makes with THE COLOR PURPLE (and he’s fully aware of this) was the decision to de-emphasize the gay relationship Celie and Shug begin developing. It’s important to remember this was dead-fuck in the middle of the 1980’s, where homophobia was actively accepted, and a federal government was mitigating an AIDS crisis essentially by pretending it didn’t exist. In that specific context, it’s a reasonable business decision for Spielberg to have made, especially when you consider he wasn’t yet known as a “social issue” filmmaker in 1985.

However, it’s a lousy creative decision, especially since that relationship is one of the most interesting and emotionally surprising things to happen in THE COLOR PURPLE’s entire runtime. Considering how much the two characters’ lives have been altered by the same abusive, arrested man, and how limited the role of a woman could really be in that place and time, Celie and Shug coming together in a romantic way feels actively defiant. But, besides that one scene, it doesn’t get referred to much, or even all that alluded to, although it hangs over the second half of the movie. I haven’t seen the 2023 musical adaptation, but it apparently features the lesbian relationship with a fuller chest, which makes me intrigued. One wonders how far into it Spielberg would go if he had it to do over again.

Anyway, Spielberg’s official response to this softening of the queerness inherent to THE COLOR PURPLE’s text is thus (from a 2011 Entertainment Weekly interview):

There were certain things in the [lesbian] relationship between Shug Avery and Celie that were finely detailed in Alice’s book, that I didn’t feel could get a [PG-13] rating. And I was shy about it. In that sense, perhaps I was the wrong director to acquit some of the more sexually honest encounters between Shug and Celie, because I did soften those. I basically took something that was extremely erotic and very intentional, and I reduced it to a simple kiss. I got a lot of criticism for that.

He stopped just short of saying he would change it, saying the kiss was “tonally consistent” with the rest of the movie, which I would agree with. But this leads us to the $1,000,000 question about THE COLOR PURPLE: was Steven Spielberg the right person for this movie?

Not to immediately retract from that intriguing, if very loaded, question, but I should mention that I am neither Jewish, a woman, or black, and thus, a lot of my insights to those particular identities are inherently going to be lacking in fundamental, inalterable ways. I also haven’t read Alice Walker’s book, although by all reports, it is a much lusher text in novel form than a movie can inherently provide.

What I can point out is that this question is not borne from the very sticky, ongoing conversation we seem to be having in modern times about “who gets to tell what stories?”, with great concern over certain types of movies being better served in the hands of underserved demographics (a line of logic I essentially agree with in terms of intent, but which inevitably leads to blatantly unenforceable philosophies of thought such as “gay roles should only be played by gay actors”). This was a genuine controversy even in 1985; the NAACP protested THE COLOR PURPLE at the time, with most of their ire pointed at its depiction of Black men, who are, as mentioned, complete dolts at best, if not active monsters. There was real concern that THE COLOR PURPLE was doing more harm than good to the culture’s depiction of Black people, especially when wrapped in the Hollywood Spielberg “feel-good” formula.

For what it’s worth, both Oprah and Whoopi have aggressively backed Spielberg on this, with Goldberg saying he made “a damn fine film”, and Winfrey allegedly saying she wished people would “shut up about it”. And I will say, it’s possible a stronger, more real, more truthful movie would have been generated from a Black director. When you view THE COLOR PURPLE as an adaptation of a seminal text, you do have to wonder if something was left on the table.

But…if you view it as a building block in Spielberg’s filmography, it feels like an essential piece of the puzzle.

One can perhaps view this section of his filmography as “the ramp-up to SCHINDLER’S LIST”. After the visceral propulsion and non-stop thrills and chills of THE TEMPLE OF DOOM, THE COLOR PURPLE slows things down and really analyzes the effects that bodily and mental trauma takes on a person. It feels like Spielberg is beginning to grow up just a tad, as well as reflecting on his own family and people’s history.

In that same 2011 interview, he stated that he’s never trying to make intellectual career decisions; he just responds to what he responds to and makes his next movie based off of that. I take him at his word on that one, which begs the question: “what did he respond to in the text of THE COLOR PURPLE”? To this reviewer, one has to wonder if he connected with the idea of looking back into the past, depicting a world where our ancestors are trapped in a system of abuse, with no legitimate way out or forward, and trying to reckon with that pain (even if, in 1985, that reckoning meant depicting a finale of redemption and reunion).

To be clear, it’s my belief that Spielberg ultimately does a good job with guiding and shaping this film, and I personally feel like a starker version of THE COLOR PURPLE might have been unbearable. The ending beat, where an older, lonely Mister sees the errors of his ways and facilitates Celie and Nettie’s reunion, feels like classic Spielbergian emotional manipulation, but I also needed it. I needed to believe there was a world where abusers can rectify their sins, cause it doesn’t happen very often in reality. I needed that escape. But, admittedly, not everyone is that needy as an audience member, and would rather have reality depicted back at them. In that case, Spielberg is absolutely the wrong guy for this job. It just kind of depends on what your particular mileage is, I suppose.

THE COLOR PURPLE’s ultimate legacy is going 0/11 at the Academy Awards, which seems weirdly fitting. Good enough to be in the running for all kinds of accolades, but with just enough flaws and questions that you can’t quite justify declaring it a winner in any category. Still, it serves as an important station in Spielberg’s career and filmography, and one that will inform the rest of the 80s, and beyond.

In that sense, THE COLOR PURPLE is a full victory.

LETHAL WEAPON: A Very (Shane) Black Christmas!

This week, we kick off A Very (Shane) Black Christmas by diving head-on into his first major holiday action hit. 35 years on, does the frenetic, edgy buddy-cop actioner LETHAL WEAPON still hold up? Given everything, can it?

A CHRISTMAS STORY. IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE. HOME ALONE. NATIONAL LAMPOON’S CHRISTMAS VACATION. WHITE CHRISTMAS.

The “official” Christmas film canon is somewhat brief, if nevertheless solid. It’s become a lucrative and expansive genre in recent years, thanks to The Hallmark Channel’s infamous churning out of approximately two billion Christmas movies a week, a business practice so hacky that making jokes about it has actually become hacky.

I think the reason the Official Christmas Movie Nice List has become so hallowed is because there doesn’t seem to be that many of them. Halloween provides so many opportunities for watch-list customization due to the fact that horror and suspense thrillers are their own year-round genre. Anything can be watched in the month of October if it passes the “spooky season” vibe check. GET OUT? Halloween movie. THE SHINING? Halloween movie. SUSPIRIA? Halloween movie. HALLOWEEN? Fourth of July movie. Just kidding. Halloween movie.

Christmas, though? Generally speaking, a Christmas movie has to at the very least have one scene that is set on the actual holiday in question. At least one door has to have a wreath or something on it. However, for most people, it seems, Christmas has to be the defining theme of the film for it to count as a “Christmas movie”. It has to be the reason any of these characters are even talking to each other. People all have their own defining lines, but generally, what constitutes a Christmas movie is limited for most.

And that’s a shame for me! One of my great cinematic joys are movies that simply use Christmas as a window dressing for the rest of its story. Christmas as a dramatic vessel, if you will. The “non-Christmas Christmas” movie. It’s an easy way to expand the field of holiday movies and include some of the best, sweetest and most fun films ever made.

And nobody in Hollywood does the “non-Christmas Christmas movie” better than Shane Black. One of the big action screenwriters to come out of the 80’s/90’s blockbuster-issance, Black stood ahead of his peers by having a palpable, almost satiric sense of humor. Where others like Joe Eszterhas made his millions with bullets and greased-up breasts (both male and female), Black wrote his scripts almost like a meta-novel; within his LETHAL WEAPON screenplay, he once described a drug lord’s mansion as “the kind of house I’ll buy if this movie is a huge hit”.

And he loves Christmas! It’s become a staple of A Shane Black Joint to be arbitrarily set during the holidays. Hell, his scripts and movies didn’t even need to be released particularly near December 25th. They can come out in March, May, whenever. Characters are still wearing Santa hats, no matter what.

To honor the strange career arc of this blessedly goofy guy, this month has been declared A Very (Shane) Black Christmas! And there’s no better place to start than the movie that really put “Black the Screenwriter” on the map, the script that featured that aforementioned mansion.

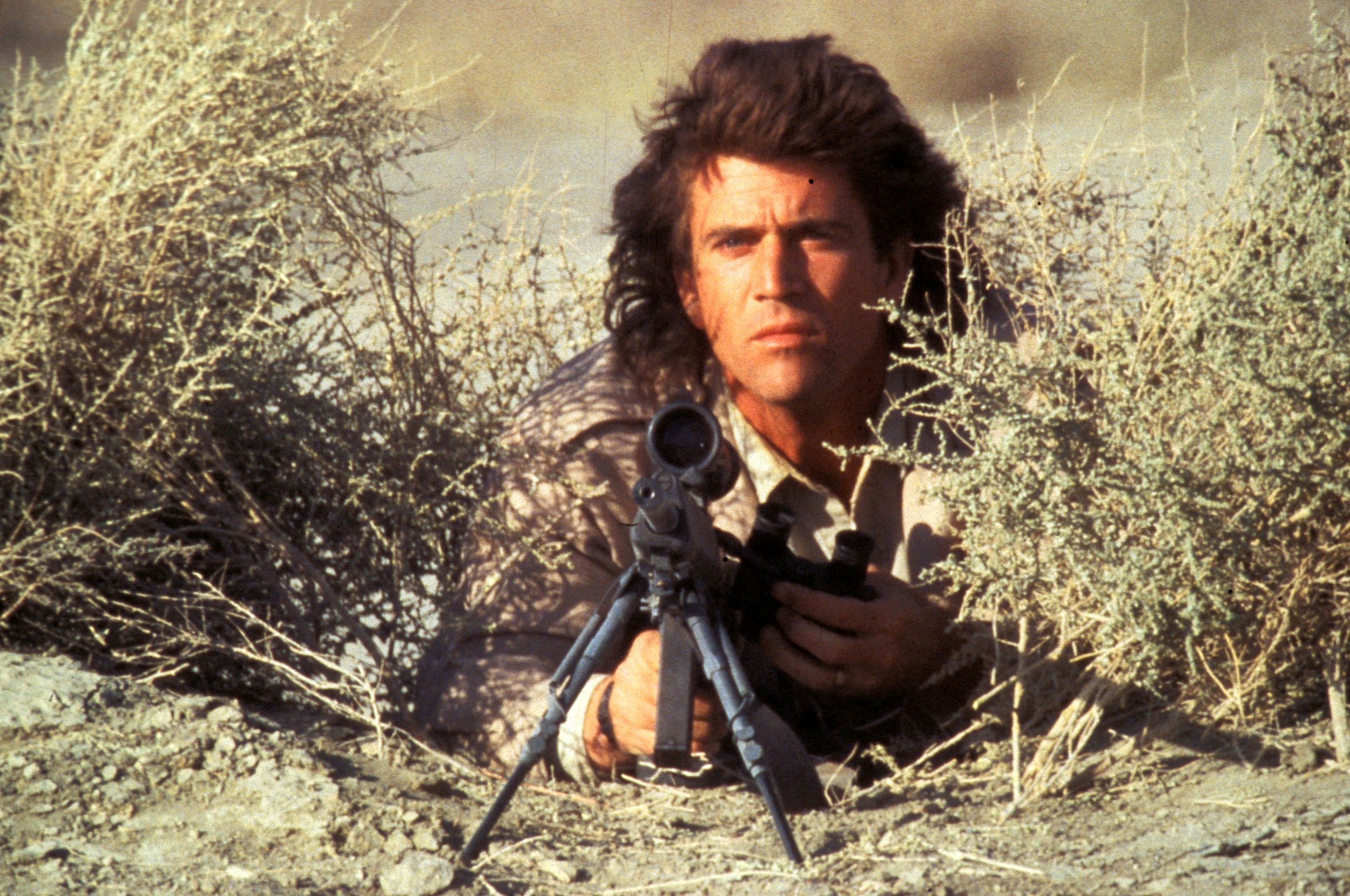

Let’s roll the calendar back to 1987 and revisit LETHAL WEAPON, starring Danny Glover and…..

….uh-oh.

Is it too late for me to ch—-

LETHAL WEAPON

Starring: Mel Gibson, Danny Glover, Gary Busey, Tom Atkins, Darlene Love

Directed by: Richard Donner

Written by: Shane Black

Length: 112 minutes

Released: March 6, 1987

The story of LETHAL WEAPON will ring familiar to anyone who’s ever seen a buddy-cop movie: on the day of his fiftieth birthday, exhausted cop Sergeant Roger Murtaugh (Glover) gets teamed up with Sergeant Martin Riggs (Gibson), a narcotics detective who has recently become dangerous and suicidal due to the recent death of his wife. Murtaugh has been tasked to team with him and determine if he’s faking it or not.

Along the way, Murtaugh has been contacted by an old friend, Michael Hunsaker (Atkins), whose daughter has apparently committed suicide. However, an autopsy shows that she was in reality fatally injected with poisoned drugs, indicating the possibility of murder. As Riggs and Murtaugh follow the trail of evidence, and the involvement of Riggs’ former Special Forces team seems almost certain, the two cops must find a way to bridge their differences and bring justice to the Hunsaker family. Can they do it? What do you think?

The “buddy cop” film genre could theoretically be traced all the way back to Akira Kurosawa’s 1949 film STRAY DOG, although the sub-genre really got going in the 80’s with 48 HRS, the BEVERLY HILLS COP trilogy and RUNNING SCARED (you know, the one with the classic duo of Gregory Hines and….Billy Crystal). The genre thrived in the 1990’s and beyond, with movies like the RUSH HOUR trilogy, LAST ACTION HERO, MEN IN BLACK and 21/22 JUMP STREET simultaneously poking some amount of fun at the genre’s trappings while also conforming to its beats (Roger Ebert once referred to these types of flicks as “Wunza” movies….”one’s a (blank), one’s a (blank)”)

The appeal of the “two diametrically opposed guys having to work together” is obvious for storytellers: the conflict is up-front, easy to dramatize and is satisfying for audiences, even if the more in-tune members know where these types of movies are going. Nobody really minds a formula, as long as it works. All a screenwriter or director really needs to do (besides really study WHY these movies work) is contribute their own personal stamp on the formula, and it’s possible you could have hit on your hands.

Enter Shane Black.

Although it wasn’t his very first script (that honor goes to SHADOW COMPANY, a movie you most definitely haven’t seen because it was never made), Black started his career hitting the ground running anyway, striking it big with just his second spec-script (essentially, a script not written as a request from a studio) that would become LETHAL WEAPON. After selling it for a quarter of a million in 1986, Black zipped away to Mexico to appear on camera in 1987’s PREDATOR. All the while, production began on LETHAL WEAPON.

The diametric difference between LETHAL WEAPON’s two central characters come from the amount of energy they carry: Murtaugh is wiped, Riggs is wired. From there, the “personal stamp” that Black provided that would set LETHAL WEAPON’s script apart from others of its ilk is its twisted sense of humor. Riggs is a very funny character at its baseline; how else to describe a guy whose plan to rescue a suicidal man from a rooftop is to handcuff himself to him and tell him they’ll jump together? But the pain Riggs carries inside of him comes from a very real place: as a result of intense loss. The fine line the movie’s main dynamic straddles between playing this situation for pathos (one of our first scenes with Riggs alone shows him nearly blowing his brains out, tears streaming down his face) and for laughs (the central “comedic beat” of the LETHAL WEAPON franchise is Riggs doing something insane and Murtaugh just kind of rolling his eyes) is commendable, even kind of gutsy.

It should be noted that the movie’s offbeat sense of humor wasn’t actually entirely the doing of Black. Director Richard Donner (years removed from the SUPERMAN drama; you should check out my podcast’s episode on that little movie for more) found the original script just a tad too dark and asked writer Jeffrey Boam to add some levity to the proceedings. Lesson learned for Black? Let’s hold onto that for now and track it going forward.

The duo of Mel Gibson and Danny Glover was put together fairly quickly after the duo dazzled Donner with a reading; they were both signed to a deal by the spring of 1986. Gary Busey was picked up for the film during a fallow period in his career (in the 80’s, this was unusual for Mr. Busey), having to audition for a role for the first time in years.

To round out the major cast, John Carpenter favorite (and star of HALLOWEEN III: SEASON OF THE WITCH) Tom Atkins was cast as Michael Hunsaker, the father of the woman who commits suicide in the film’s ope ing sequence. Finally, long-standing R&B legend Darlene Love was selected to play Trish, Murtaugh’s wife. For whatever reason, the four LETHAL WEAPON movies constitute the vast majority of Love’s filmography. The only other two movies she appeared in as somebody other than herself was in 2019’s HOLIDAY RUSH and in 2020’s THE CHRISTMAS CHRONICLES 2. So there you go.

As a movie, LETHAL WEAPON holds up about as much as you might expect, although it’s difficult to completely detach it from its most obvious Christmas action movie* competition, DIE HARD, which came out about a year later. That Bruce Willis vehicle has sort of taken that very specific crown and has never really looked back, its status no doubt bolstered by having its first sequel ALSO set during Christmas.

* Look. everybody, I don’t want to re-litigate the most annoying piece of holiday discourse since that one year everyone was obsessed with figuring out whether “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” was written in support of sexual assault or not, but DIE HARD is obviously a Christmas movie. Or it isn’t! Who cares! Eye of the beholder! I’d rather stick a gun in my mouth Riggs-style than ever get into an actual argument with somebody about this.

Essentially, LETHAL WEAPON suffers from not being DIE HARD, maybe the best action movie ever made. Oh, well! It’s still a good time (if edgier than you remember), with Gibson’s high-wire “loose cannon” act playing well against the straight-faced, beleaguered Glover. At the end of the day, it’s about those two, and you never get tired of watching them, the real signifier of success for what essentially amounts to another entry in the buddy cop genre.

And let’s not forget the real reason for the season. The Christmas of it all! Even though Christmas doesn’t really factor into the plot, the trappings of the holidays are everywhere. The damn opening scene (where a topless female jumps out of the window of a high-rise, plummeting to her death) is scored to the tune of “Jingle Bell Rock”. One of its most somber “we’re gonna get her back” moments takes place in a living room, with Riggs and Murtaugh framed by a family Christmas tree.

So, does anything hold LETHAL WEAPON back? Well, there’s that guy in the middle of it all.

I’m afraid we have to talk a little bit about Mel Gibson.

Here’s the funny thing about “cancel culture” (a phrase I sorely wish had never entered the cultural lexicon, if only to avoid having to hear people twice my age complain about it, please also see “woke”): who exactly is “cancelled” is eventually up to the individual. For instance, despite having apologized and technically (TECHNICALLY) not having committed a crime, I personally haven’t been able to return to Louis C.K.’s work, despite him being one of my very favorite comedians even as recently as five years ago. Yet, after a brief respite, he’s still out there winning Grammys and selling out shows. He’s cancelled to me, but not for many of ye.

On the other hand, despite wishing he had made better choices, and still sort of waiting for another shoe to drop, I’ve been able to still enjoy John Mulaney’s new material just fine. Not everybody agrees with me on that, deciding the way he’s decided to deal with his addiction has ruined the “harmless man-boy” facade. The facade is really important when you’re a celebrity! Once it’s gone, people don’t always come back, even if you’ve owned up and moved on.

So it goes for Mel Gibson and, boy, lemme tell ya, when I started putting this all together, I knew this would be a delicate conversation. But, I didn’t anticipate his particular….uh, anti-Semitism to become in vogue with so many other celebrities now in 2022. Seeing a certain rapper/mogul/masked man completely melt down has made me reflect quite a bit and really think about how much I want to let Gibson off the hook even now.

The thing is, when people think of “Mel Gibson controversy”, most people remember his 2006 DUI meltdown that led directly to his anti-Semitic outburst, as well as his 2010 leaked voicemail viciously berating his ex-girlfriend by using maybe the one word you really cannot use. But trouble for Gibson started all the way back in 1991 with an interview with Spanish paper El Pais, where he made some, er, colorful statements about homosexuals.

I bring this stuff up not to moralize or condemn (after all, the El Pais interview is over thirty years ago now), but to give context as to why some people aren’t so comfortable enjoying Gibson’s movies anymore, and probably never will again. It’s true that essentially every public transgression in his life can be traced back to alcoholism and he’s admitted as much. But stuff like an A-list star dropping the N-word (yes, it was from a voicemail that we absolutely should never have heard, but the fact that he was willing to say it when he thought nobody was listening is revealing), or a devout and open Catholic going off on Jewish people in a drunken rant (he’s characterized it since as an attempt at “suicide by cop” which….eh) remains startling for many people. Being straight about your addiction can only extend so much grace.

What burns me is that, despite everything, Gibson really did earn his A-list status in his day. It’s not really deniable. Earlier this year, my wife and I watched SIGNS for the first time in maybe twenty years. It’s definitely the first one of M. Night Shyamalan’s major films that showed just the teensiest cracks in his facade, what with the kind of dunderheaded water twist (although I’ve also always hated how Joaquin Phoenix’s character needed to be told the words “swing away” in order to be motivated to pick up a baseball bat and start beating the shit out of an alien….never mind).

But! I was struck at the kind of performance Gibson was giving as Graham Hess, a reverend whose faith has been fundamentally shaken by the gruesome death of his wife (recurring theme for Gibson characters?). It’s a quiet performance, punctuated with awkward, momentary bursts of emotion. It’s mostly all internal, under the surface. It’s damn near perfect.

Compare that with the wild-card energy of LETHAL WEAPON’s Martin Riggs, who is just as comfortable pointing a gun at his own head as he is pointing it at a perp. There couldn’t be two different people than Hess and Riggs, and they both were embodied by the same man.

All of that is what makes him so frustrating to talk about now. You almost wish he was a little more inept as a leading man; it would make it easier to write him off completely. But you can’t! Not entirely. Gibson, at his peak (and even a little after), was undeniably watchable. At least to me.

I also hesitate to hand-wave reconciling his act with his actions away with that “good artists do bad things, get over it” credo, because that’s usually just code for “I’m not giving this particular person up, and I don’t want to be made to feel bad for it”. Again, everybody’s line is different, and it’s fruitless to argue with people about where their personal line ought to be placed. As we’ve observed over the past couple of years, anti-Semitic rants and N-word usage in fits of rage are hard lines for many. Telling those many to get over probably isn’t going to be a long conversation.

Unfortunately, we’ve all had to come to grips with SOME favorite celebrity having their illicit pasts come to light in the For myself, I find it easier to deal with good art from bad people (as I happen to define it; I can’t work off of somebody else’s barometer and neither should you) if the art happens to exist in a time where nobody knew it yet (or at least nobody in the public). It’s not the most perfect test in the world; how does one adjust for changing in social mores (there’s a reason the El Pais wasn’t a deal-breaker in the early 90’s in the way it almost certainly would be now)? What if that previous art has the air of an offender hiding in plain sight (the aforementioned Louis C.K., even….W**** A****)? Your mileage may vary.

Somewhat conveniently for me, LETHAL WEAPON passes that smell test, having comfortably been released in 1987. You may not agree. That’s okay.

At the end of the day, when it comes to celebrities who publicly, spectacularly show their ass, we all have our own guiding principles and dividing lines as to whether not you can ever really enjoy them or not.

It’s a little like how we decide what a Christmas movie is or not.