Recent Articles

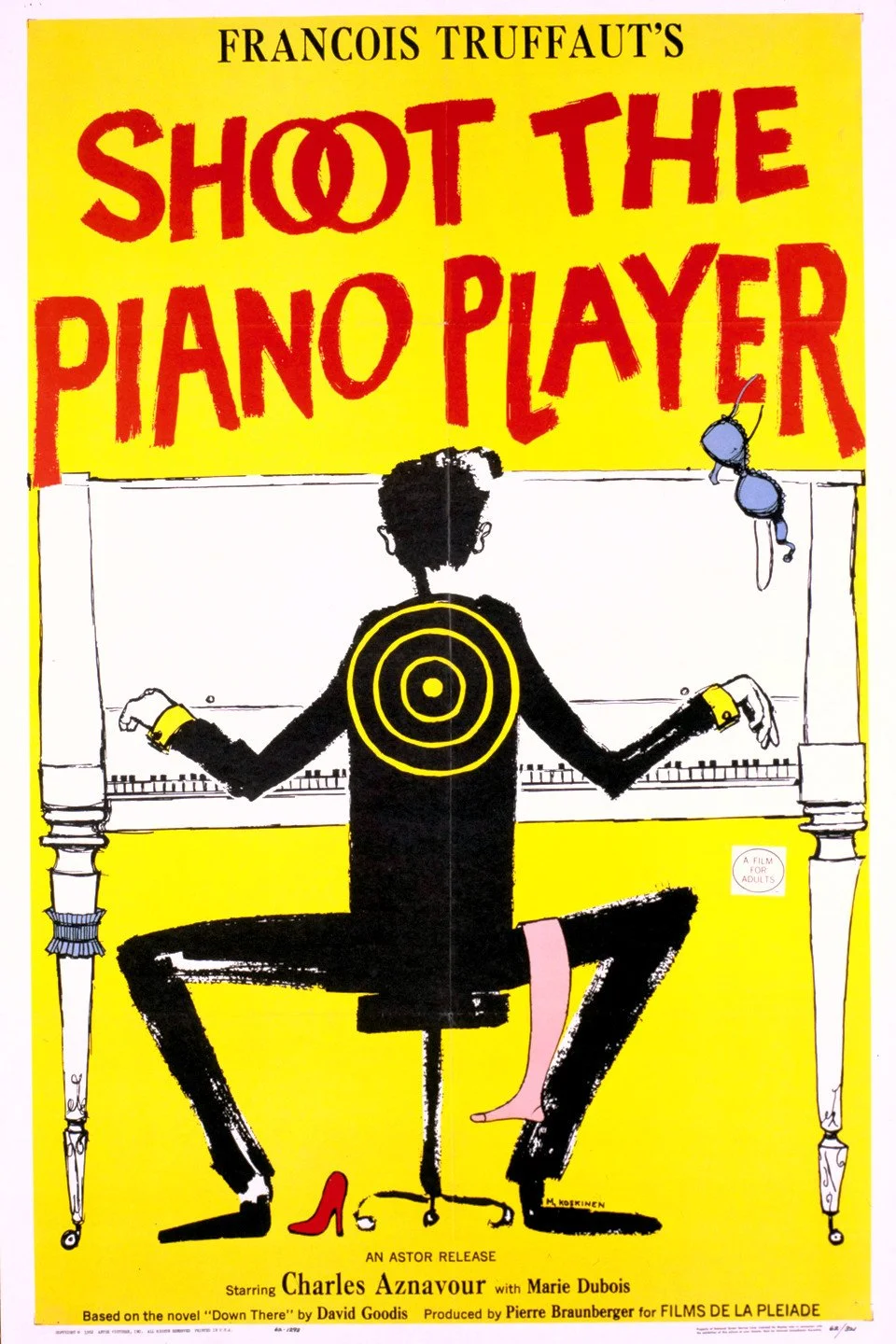

Film School Weekend: SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum.

A late programming change allows me to gush about this unexpected masterpiece.

So, full disclosure this weekend.

My initial plan was to devote this space today to Francois Truffaut's third film, JULES AND JIM. After talking a couple of weeks ago about his trailblazing debut, THE 400 BLOWS, it felt like a good idea to jump over to his next nearly-larger-than-life-in-reputation film, his 1962 saga about two friends who end up falling in love with (and being seduced by) the same woman over the course of twenty-five years.

And, indeed, I ended up watching it and, as everybody says, it's great! It features a character-driven plot line that is at once endlessly complex and totally heartbreaking, not to mention innovative (Martin Scorsese devotes a whole section of his Masterclass to the use of voiceover in its opening minutes). To be honest, I'm not sure I fully absorbed the whole thing in the lone viewing of it I have under my belt; it constantly surprised me, which meant I spent much of the time recalibrating my expectations throughout. This tends to make expounding on JULES AND JIM at any length a little tricky since, well, I'm not sure I precisely know what I'm talking about yet.

But, the intent was to write about it, so prepare to write about it I did. And then I found I had a spare eighty minutes on my hands one night. And I noticed that, between Truffaut's first and third films, there sat another movie, SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER. It seemed like a quick watch, and I thought maybe it would help inform me as to his arc between 400 BLOWS and JULES AND JIM. What was the harm?

So I watched it.

And I was blown away.

Sorry, JULES AND JIM.

SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER (1960)

Directed by: Francois Truffaut

Starring: Charles Aznavour, Marie Dubois, Nicole Berger, Michele Mercier

Written by: Truffaut, Marcel Moussy

Released: November 25, 1960

Length: 81 mins

Intended as a tribute to the 30's and 40's American B-movie, the initial thrust of SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER will seem familiar to any other noir aficionado. We start with a man clearly on the run from some bad people, and follow him briefly as he stumbles into a lively piano bar. He insists on an audience with the piano player, who we quickly learn is his brother. There's clearly a history that the piano player, Charlie (Aznavour) is running from; Charlie isn't even his real name, it's Eduoard. Regardless, he wants nothing to do with his brother's affairs. Alas, as many hapless heroes of noir often find out, trouble finds him regardless. His brother has ripped off a pair of gangsters and is now trying to elude his fate. Alas, just by contacting Eduaord, he's gotten him involved.

Along the way, we learn more about Charlie/Eduaord through his relationships with the three major women in his life. There's his former wife Therese (Nicole Berger), whose decisions we learn about in flashback and inform his new identity as Charlie. There's Clarisse (Mercier), a prostitute who sees Eduoard often and is raising her little brother Fido. Finally, there's Lena (Dubois), the piano bar waitress who's slowly falling in love with him and finds herself in the middle of his run-ins with a pair of gangsters.

Sure, it's all fairly rote, even by 1960, but this movie isn't necessarily trying to break ground by its plot. No, where it really makes an impression is in its storytelling and directing technique. Simply put, SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER is probably one of the most playful movies I've ever seen.

The movie seems to change genre at will every few minutes or so. Sometimes it's a noir tribute, sometimes it's a gentle comedy, sometimes it practically borders on broad farce, sometimes it's a heightened melodrama. And it manages to do it with such ease, changing gears practically right before your eyes. I'm sure there have been many films before and since that have threaded this needle before, but I've rarely seen a movie succeed so well at attempting so much.

That's not to say SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER is fully groundless; when the movie aims for both pathos and drama, it's actually genuinely affecting. There's a whole section in the middle where we really get to learn and see Eduoard and Therese's married life, with all the jealousies and perfectionisms that come with living with a professional concert piano player (as well as those costs). But Truffaut isn't afraid to swing for the fences with frequent pauses for things like bawdy songs, or wild punchlines that come out of nowhere; no joke, SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER contains maybe one of my favorite unexpected jokes ever, after one of the gangsters swears to the truth of his recent statement, lest his mother should drop dead.

This was all an active choice on the part of Truffaut; he found a lot of success with THE 400 BLOWS and rightly so. But there was a common sentiment that it was very French. Wanting to show that he could have a varied and fruitful career, Truffaut went the total other way with his follow-up feature, going for something with uniquely American sensibilities. The screenplay is officially credited to Truffaut and his 400 BLOWS collaborator, Marcel Moussy. But, in truth, Moussy couldn't find an entry point with either the script nor its source material (David Goodis' novel Down There). Moussy wanted to ground the characters, while Truffaut insisted on keeping things loose and abstract. Moussy left the project soon thereafter.

Truffaut was right to stick to his guns on this one. He had an ethos for putting SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER together; "I wanted to break with the linear narrative and make a film where all the scenes would please me. I shot without any criteria." And you can feel him doing just that, although it does feel like if there were criteria, it might be "pay homage to 40's Hollywood at every turn". There are apparently references to the works of director Nicholas Ray and Sam Fuller crammed in there, as well as more obvious references to stuff like The Marx Brothers (one of the brothers' names is Chico) and the filming techniques of silent films (the use of irises pervade throughout).

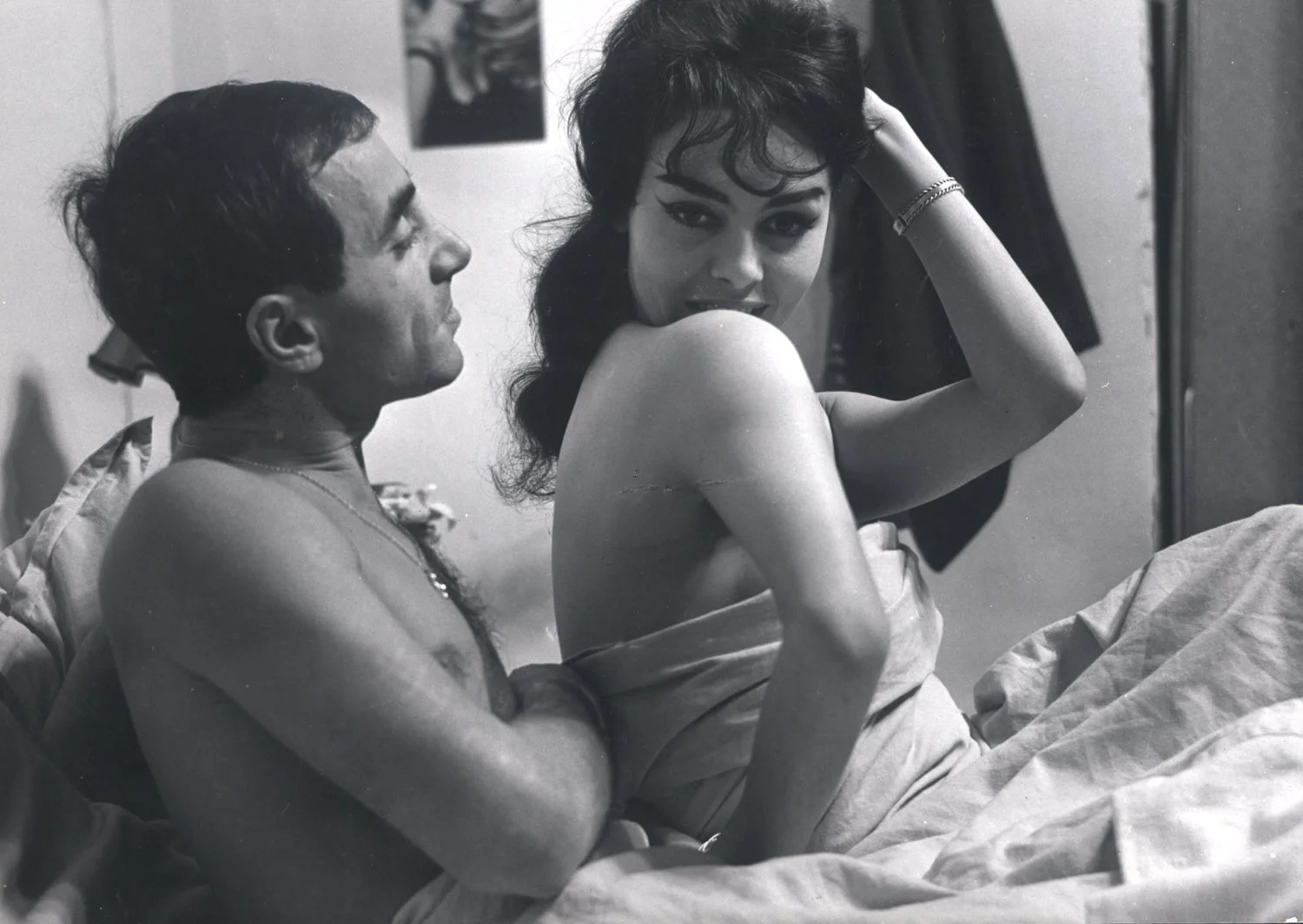

It should be noted that none of this would work without the abilities of the cast at its center. Aznavour is perfect as the man in the middle, the titular piano player. He plays everything straight, which is an informed move. As a result, the comedy around him seems that much funnier, BUT when it's time to play the drama, you easily buy it. He has one of those faces and sets of eyes that connote whole histories without having to write a single line of dialogue.

The three women are all great as well; what's fun about them is that they each provide a different personality type. Clarisse is sweet and sexy, Therese is subtly acidic and devastating, and Lena is hopelessly romantic. Special mention, though, should go to Marie DuBois, who plays Lena and endows her with a hopefulness that the other characters don't quite have. The reason I point her out is that she would go on to star in....JULES AND JIM! If you've never seen it, suffice to say she plays a completelydifferent type of character and philosophy, an example of the versatile kind of player you don't always see in the modern day.

Listen everyone, I don't know what else to say without beginning to give stuff away. SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER is a damned delight, alright? How often do you see a filmmaker's career take such an interesting turn just two films in? Seriously, compare this to the feel and style of THE 400 BLOWS, a movie that's so controlled and so singular in its focus. It's a coming of age story that's told so simply, it's almost not apparent at first what made it so special, either then or now. The particular magic there is in its subtleties and the invisible hand of its creator.

Not SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER. With this one, you're fully aware of the person behind the wheel, and he's having a blast! And so are you as a result. So, please, check it out. It's available for streaming right now on the Criterion Channel, as part of that massive 44-film French New Wave collection they dropped earlier this month. It goes down so easy and you're gonna have a good time.

And...that'll do it for French New Wave this month! I'll be pivoting to a new series that's a little closer to home and maybe a decade more modern next week. See you then!

Film School Weekend: Breathless

"There was before BREATHLESS, and there was after BREATHLESS!"

Few movies in the French New Wave canon loom quite as large as Jean-Luc Godard's debut (by the way, not to go super parenthetical in the very first paragraph, but the fact that we've already covered two directorial debuts that made such an impact to this particular moment in film history would indicate, I think, just how large a burst of energy the French New Wave really was. Almost like a whole generation of filmmakers were waiting and waiting and waiting, and then when they finally got the chance, BAM! Anyway.)

There are reasons for its strong legacy. BREATHLESS, a sort-of riff on American crime films, hits the ground running right at the start and never really lets up from its pace until the end of its ninety minutes. As well, it features two characters who are aimless in their own ways, and kind of feed off of each other, something that was a little unusual for its time.

And it had style in so many different ways. It had literal style; Jean Seberg's shirts (both the striped one and the one reading New York Herald Tribune) have been recreated and are available to purchase on a plethora of websites to this day. But it also had cinematic style, most famously its unconventional usage of jump cuts, sometimes several in a row within the same scene.

BREATHLESS permeates through pop culture to this day, with references to it being found in diverse sources such as Brooklyn Nine-Nine and Ghost in the Shell. Naturally, I hadn't seen it, which made it a natural choice this month for Film School Weekend.

So....how does BREATHLESS stand up to its almost overwhelming pedigree? Does it stand up to it?

Hop in, let's find out.

BREATHLESS (1960)

Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard

Starring: Jean Seberg, Jean-Paul Belmondo

Written by: Godard (story by Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol)

Length: 87 minutes

Released: March 16, 1960

BREATHLESS kicks things off with perhaps the greatest opening line in film history ("After all, I'm an asshole") as we meet Belmondo's charming, nihilistic criminal Michel. He's on the run from the law after stealing a car, which leads to him suddenly shooting and killing a police officer. He hightails it back to Paris and hides out with an American girlfriend of his, Patricia. His plan: get her to run away with him to Italy before the law catches up with him. Eventually, an inspector will make Patricia have to make a choice about her mysterious, free-wheeling man who, by the way, she may now be carrying the baby of.

What's really interesting about BREATHLESS is that the above all makes the film sound fairly plot-heavy, and not altogether separate from an American crime film or noir from the 30's or 40's, perhaps the kind of Humphrey Bogart-starring vehicle that Michel himself would have enjoyed. But this movie really isn't about the plot, nor does it feel American. Instead, it makes its mark in the character scenes, these long, more steadily-shot sequences where Michel and Patricia are talking about anything and everything.

Godard really wants to draw out the fundamental differences between Patricia, who is at a crossroads in her life and desperately searching for meaning and purpose, and Michel, who has long ago found his meaning and purpose: the lack and absence of meaning and purpose altogether. He likes watching movies like THE HARDER THEY FALL and then stealing cars and acting like a general piece of shit ("after all, I'm an asshole").

For a wide a gulf as this difference in philosophy is, you sort of get the appeal on Patricia's end. Admittedly, for someone who's looking for something, the option and permission to stop looking entirely must feel quite alluring. And for Michel, being with someone who is looking for something more must be so foreign as to be completely captivating. The chance to exist in each other's head spaces appears to be fulfilling some sort of psychological need for the both of them.

This brings us back to those infamous jump cuts. There are a surprising amount of theories as to their express purpose, some even suggesting the jump cuts were placed in random spots by Godard, either in an act of spite or desperation. Other explanations offered get deep into editing theory, which is way beyond my education and knowledge base. In my estimation and observation, these cuts seem to occur mostly in scenes where Michel is in transit, either with himself or with Patricia in tow. We're in Michel's territory, his mind-set, and we now have to move a million miles an hour, even when we're sitting in the back of the car. Notice, though, how much the movie seems to settle down when we're in Patricia's apartment. Now we're in her territory and, thus, in a less kinetic, fast-paced space. Whether it was the true intent or not, it felt to me like an indicator as to whose eyes we were supposed to be experiencing a certain scene through.

As you might expect with a sixty-year old movie that was so well known for its frenetic editing and pace, BREATHLESS suffers a little bit now that we have entire generations that have been born and raised after the advent of MTV. A movie that probably seemed incredibly fast, especially when compared to the more modest editing practices of many films up to that point, now seems like nothing compared to the average movie you could find buried in an Amazon Prime category.

That said, I'd argue that, when BREATHLESS is really up and running, some of its jump cuts create a pace that still reads as unusually fast, even in this age of ADD. I'm not kidding when I say there are some scenes of Michel and Patricia driving in a car where it feels like there's a cut every second for several seconds in a row. Just as an example, there's the really famous sequence where Michel, driving Patricia to an appointment, starts listing off parts of the female body he adores, each accompanied by a new jump cut of Patricia sitting in the passenger seat. They're not even shots of particular body parts, just a fresh look at her for every sentence fragment. This is a pace that is usually reserved now for bad modern action sequences, not something so relatively stationary.

This feels like a good time to mention that I stand as a little mixed on BREATHLESS as a whole. Despite how interesting it was to watch, I found it a little difficult to settle into in the way that some of my favorite movies do (side note: something I've noticed when watching a fundamental classic for the first time is that I often experience...not an out-of-body experience, exactly. But almost like I'm watching myself watch it? Like my thought process is more, "here I am, watching RAGING BULL". Almost as if the movie looms so large that I can't focus right away. Does anybody else experience this phenomenon?). With a few days to reflect, I have to wonder if it's because its true innovation was technical rather than thematic. I can usually tell when a movie resonates with me when the analysis flows through me even days after seeing it. This time, I had to look up certain things to jog my memory. C'est la vie.

However, there's still a major take-away that made it worth my, and your, time. Once again, what I want to draw attention to is a performance within BREATHLESS, this time one given to us by Jean Seberg. In a way, she has the harder role between her and Belmondo. Belmondo gets to be extroverted, forceful, the cool Humphrey Bogart wannabe. By comparison, Patricia is often more passive, at least externally. But she is the one where the change occurs in the story, at least it seemed to me. She is the one who has to evaluate the unique, aimless worldview of her criminal lover and ultimately decide to reject it by turning him in, even as she doubts herself all the way to the ambiguous closing moments.

Because Patricia does at least have goals and ambitions, her being an aspiring journalist and all. Michel is happy just to be an asshole, living his life like a Bogart film without much care and regard to who gets hurt along the way. Yet she loves him anyway, maybe too tempted by his disregard.

Seberg is able to register all of these complex emotions without doing much at all. I've already gushed last week how much I latch on to those who act without acting, whose entire inner life is so clear and consistent that the performer can just sit there and you follow along completely. Well, Seberg delivers on that front. She's someone who lived a short, complicated, fascinating life (fun fact: she was a particular target by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI for her support of the Black Panthers), and I highly recommend Karina Longworth's series about it as part of her bigger You Must Remember This podcast if you're interested in hearing more.

Overall, despite how interesting BREATHLESS was to watch and write about, I was surprised how much of it has faded away from me a few days later. Maybe it's that lack of focus on story that caused me to walk away with less than it felt (this is something I'm still adjusting to in other genres, such as giallo). Or maybe it's the fact that it's hard to shake the feeling that it's mostly an exercise in style. Divorced from its moment in time, its legacy might be more what it would go on to inspire more than it actually is.

Jean Seberg, though, man.